Should your ads directly attack your competition?

Should they make direct comparisons between your product and service and the competitors?

Or should you simply tout the good qualities of your Brand and ignore the competition?

Short Answer:

Your ads will always be comparing your offering to reasonably considered alternatives. The only questions are:

- Whether the comparison will be implied and indirect, or

- Explicit and direct (or possibly even named).

But before discussing how to determine which type of comparison your ads should use, let’s look at some examples of each, starting with…

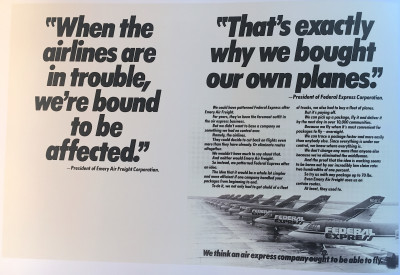

Explicit and Direct Comparisons

The “patron saint” of comparative advertising is Carl Ally of Ally & Gargano fame.

It’s been said that: “Ogilvy gave advertising dignity. Bernbach gave it humanity. Carl Ally gave it teeth.” And you can can see why from these examples:

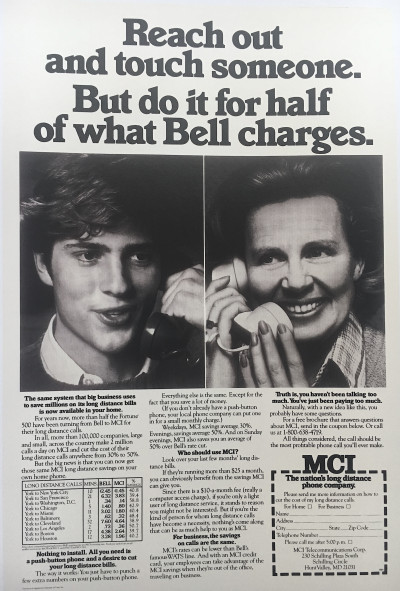

And here’s another direct-call-out competitive TV ad for MCI (also by Ally & Gargano):

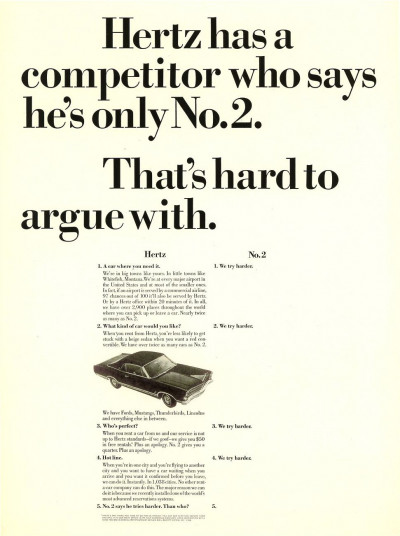

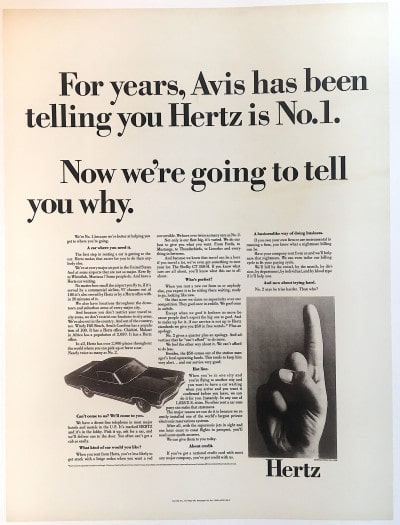

And of course, there’s the work Ally & Gargano did for Hertz, after Hertz got their butts handed to them by Avis’s famous “We Try Harder” campaign.

See, Bernbach’s “We’re only #2, so we try harder” positioning for Avis hard brought the company to within a few percentage points of equaling Hertz for market share — until Hertz hired Ally & Gargano and they took that “#2” positioning and beat Avis with it like a stick.

If you’ve ever wondered why Avis stopped running their “We’re #2” campaign, now you know why.

Within a few months of launch, Hertz’s direct call-out campaign not only forced Avis to abandon their till-then-successful advertising, but reversed the sales trends and returned Hertz to their dominant share of market.

One lesson from this is that it takes a powerful and effective advertising campaign to counteract a powerful and effective advertising campaign.

What About Indirect and Implied?

But did Ally & Gargano only do direct call-out ads?

Of course not. Here are two of my all-time favorite TV ads from them that don’t use direct call-outs of competitors:

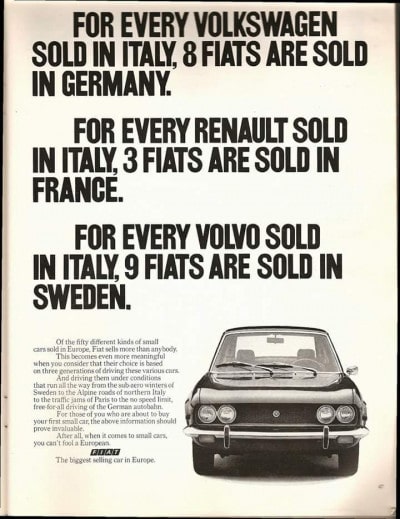

You’ll notice that these ads focused on the superiority of their service and product respectively without directly calling out the competition.

And this is why I wrote at the beginning that your ads will always be comparing your offering to reasonably considered alternatives.

When it comes down to it, you are either offering:

- The same or better quality or experience for less money, or

- Better quality or experience for more money

And more often than not, you’ll find yourself in the latter category.

But In either case, making people believe your claims involves some type of comparison, either implied or direct.

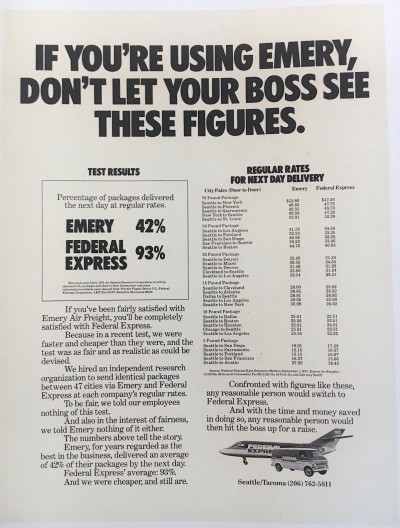

By the time that FedEx ad ran, they’d already beaten the pants off of Emory, so there’s no more need for comparison. They were in a class of their own, and simply had to take more business away from regular-old non-express shipping, for when packages “absolutely, positively had to be there overnight.”

Similarly, that Dunkin Donuts ad was mostly about how great their donuts were. Now if you were enjoying the comedic performance and wrapped up in the story, you probably missed this, but there were still some digs thrown in there about “supermarket” donuts. Which means the comparisons were largely indirect and implied. But they were still there.

If you’re going to make a special trip and drive out of your way for donuts, they’d better be worth it, right?

So when should your ads focus on direct comparison vs. indirect?

There are three questions you should ask yourself:

1) Are the facts on my side?

There’s an old legal proverb attributed to multiple famous personalities with multiple variations to be found online, but it goes something like this:

“If the facts are on your side, argue the facts. If the law is on your side, argue the law. And if neither the facts nor the law is on your side, sing and dance, holler and shout.”

When you actually HAVE a clear, demonstrable, factual comparison to make, you should make it.

And because specifics are more believable than generalities, you should be as specific as possible when making that comparison.

That doesn’t necessarily mean you should name your competitor outright, but you should leave little doubt as to who’s coming up short in the comparison.

2) Are you the up-and-comer or rebel, or are you already the established choice?

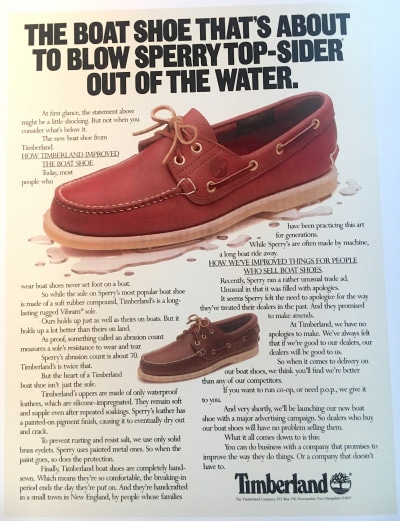

If you’re the underdog rebel, comparative advertising is generally a good thing. That’s why MCI hammered Ma Bell so hard, why FedEx ripped Emory to shreds, and why 80s era Timberland took such sharp aim at Sperry Top-Siders.

On the other hand, if you’re king of the hill, punching down isn’t normally a great idea — unless you are responding to a genuinely effective challenge, or to remind people why “just as good for less” is largely a myth (as in the Hertz example above).

In the class-leader case, it’s typically better to leave your comparisons implied and indirect.

There’s a reason it was Pepsi that did the Pepsi Challenge, and not Coke, who simply reminded you that they were “the real thing.”

3) Are your customers Maximizing or Satisficing?

The great myth in advertising is that every buyer is looking to utterly maximize and optimize every purchase, regardless of the time and attention required to do so.

But nobody has that much time or attention. So the vast majority of purchases are satisficed instead of optimized.

If you’re unfamiliar with that word, Satisficing means finding a “good enough” solution you can trust with a minimum of time, effort, and attention.

In other words, people have a problem and they want a “good enough” solution that’ll remove that problem and allow them to get back to their regularly scheduled life with a minimum of effort.

If you are selling considered purchases or enthusiast type (aka, “Sexy”) products that are maximized — AND if the facts are on your side AND you are the up-and-comer — then by all means make explicit and direct comparisons.

Do your best Ally & Gargano impersonation.

If, on the other hand, you sell something bought via satisficing, then make your comparisons indirect and implicit.

Make yourself the “sure thing” solution that people can trust. The honest goods.

And leave the idea that other options aren’t so sure or so honest implied.

In other words, practice a bit of Ugly Duckling Advertising.

I hope that helps you understand the pros and cons of comparative advertising and when and where to employ it. If you still have questions, or want help making such a choice, feel free to contact me — I’m happy to help.

- Are You Paying for Too Much for the Wrong Keywords? - July 15, 2024

- Dominate Your Market Like Rolex — 4 Powerful Branding Lessons - July 3, 2024

- Military-Grade Persuasion for Your Branding - June 25, 2024