The advertising world of the 1950s was not so different from today’s.

And not in a good way.

Data, research, and science reigned supreme on Madison Avenue during the 50s. Motivational Research, Consumer Research, subliminal research, and psychological studies thrived.

Clients were pitched with assurances that “tests proved that…”

The downside? No room for creativity or humanity.

It’s why Bill Bernbach, then VP and Creative Director at Grey Advertising, wrote and circulated the following memo as a call to arms for change:

“There are a lot of great technicians in advertising. And unfortunately they talk the best game. They know all the rules. They can tell you that people in an ad will get you greater readership. They can tell you that a sentence should be this short or that long. They can tell you that body copy should be broken up for easier and more inviting reading. They can give you fact after fact. They are the scientists of advertising. But there’s one little rub. Advertising is fundamentally persuasion and persuasion happens to be not a science, but an art.”

Frustrated, Bernbach left Grey Advertising to start Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) and kick off “The Creative Revolution” in advertising, from which would come some of the best whisky ads ever made.

But before I get to that campaign, let me ask: doesn’t Bernbach’s memo sound exactly like today’s marketing world?

A world in which all things digital, metrics, data — and now “big data” — reigns supreme? Where the tech weasels all talk the best game while producing crappy ads and disappointing results?

Maybe the creative revolution of the 60s still has some lessons for us here in 2020, right?

So let’s get to that campaign.

Background to DDB’s Chivas Regal Campaign

In the 1960’s Seagrams acquired Chivas Regal only to find brand sales languishing.

Chivas was losing out to competition from “lighter” scotches, such as Cutty Sark and J&B Rare.

In the face of this sales challenge Edgar Bronfman convinced the company to commit to new packaging and a new ad campaign.

They hired Bernbach and the marketing lessons start right at the beginning of that relationship

Lesson #1: The right relationship between client and marketer

Bill Bernbach told potential client and Chivas Regal owner Sam Bronfman:

“I think I ought to tell you that I’ll never know as much about your business as you do. How can I? You built it, you breathe it, you dream it.

But you have to understand I’m in a different business to you, even though it involves your product. And I know my business better than you?”

Bronfman’s reply: “You mean together we can do a great job? OK, you’ve got the account”

Trust. The more creative and powerful the work, the more trust is required. And that relationship has to be begun correctly to work out.

Advertising is storytelling. And with all great stories, beginnings — origins — are determinative.

Lesson #2: Don’t Proclaim — Evoke!

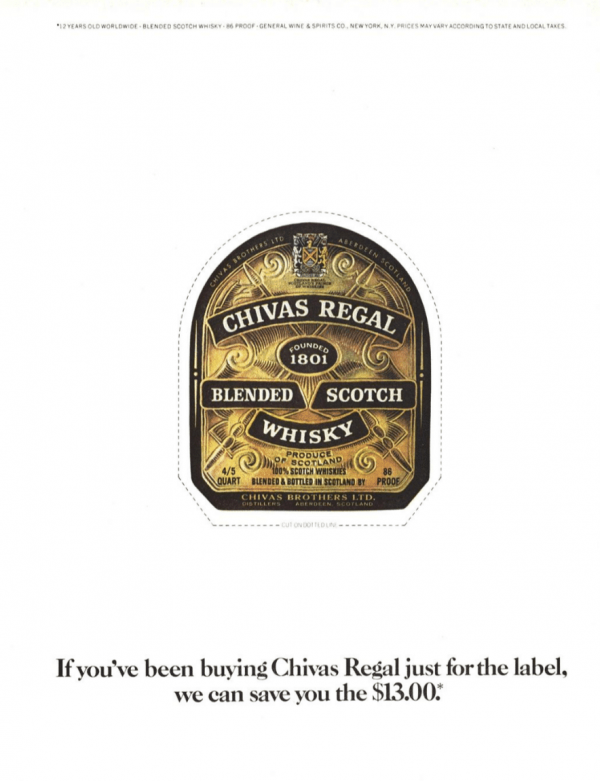

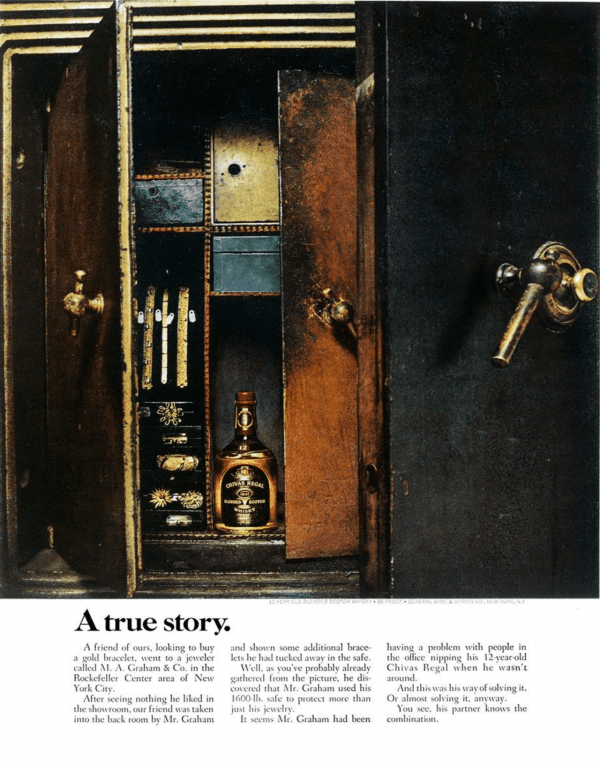

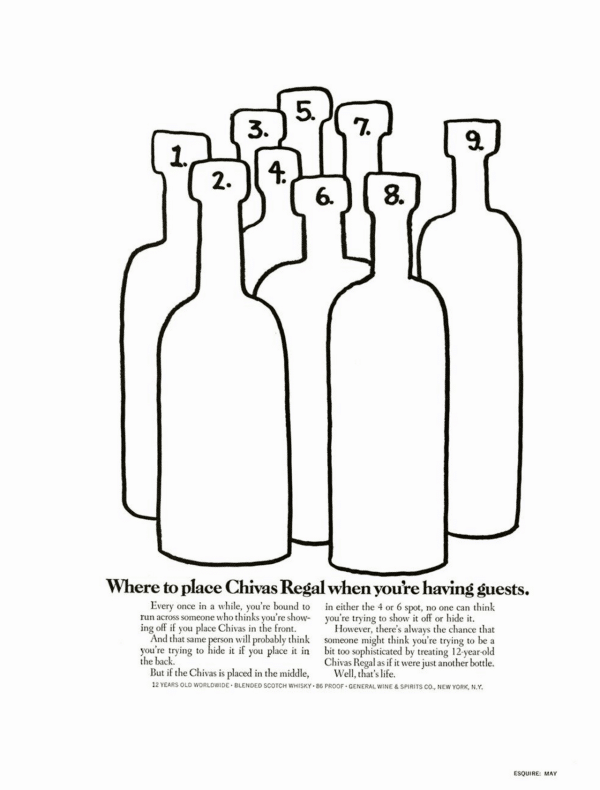

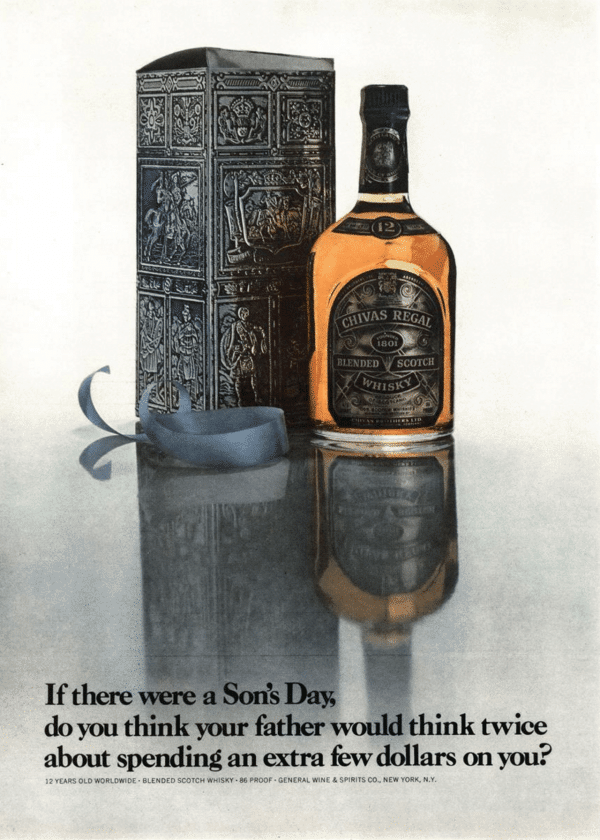

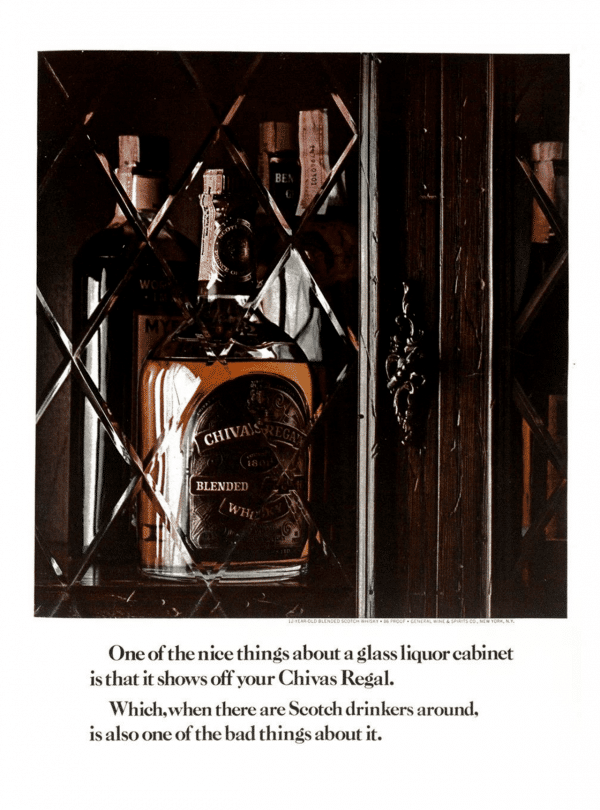

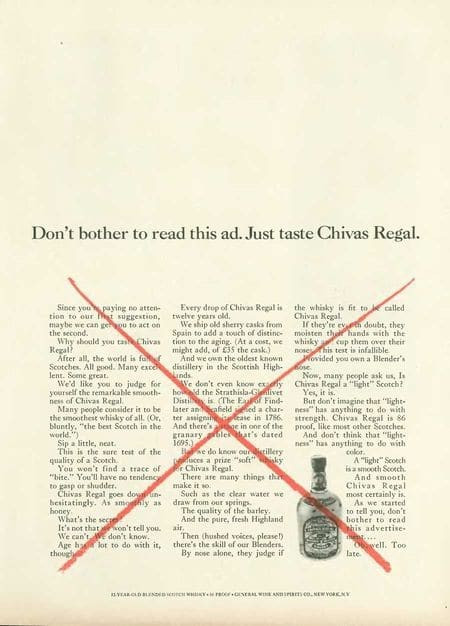

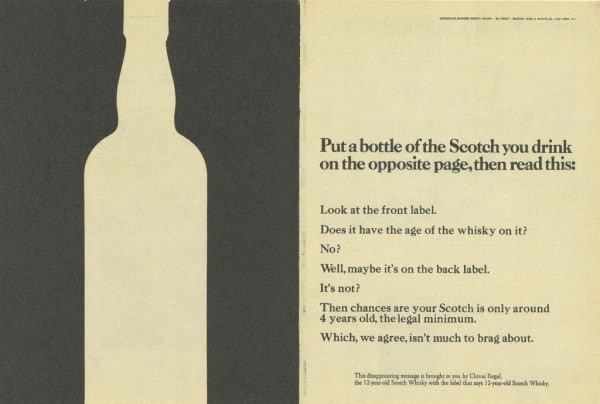

OK, first, check out the ads:

So this is just a smattering of ads from a very successful and long running campaign, but you probably get the gist.

The ads didn’t proclaim Chivas to be the best.

The ads presume that the reader already knows that Chivas is super premium.

Indeed, the ads tell a story that you can only understand if you first accept that Chivas is, in fact, the best of the top shelf whiskeys

More importantly, the ads always evoked an emotional “reality hook” from the reader. They evoke — and provoke — a reaction from you more than they try to push information at you.

When you’re the owner of a company — a company “you built, you breathe, and you dream” — it’s hard not to want to TELL people all the details.

But telling people the truth about your product or service won’t persuade them. You have to get people to realize that truth for themselves.

And these DDB ads do that beautifully.

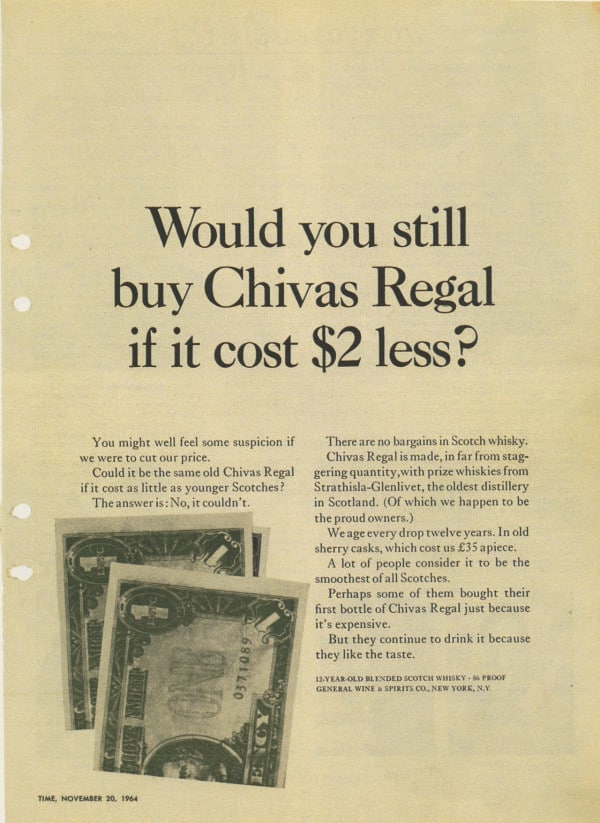

Except, of course, the ads were suggesting the truth a bit more powerfully than the facts would have allowed.

At the launch of the campaign, Chivas wasn’t seen as premium and they weren’t category leader. Yet the cocksure attitude and subtle persuasion of the ads compelled readers to assume they were — which soon led the facts into alignment with the ads.

Lesson #3: Personality trumps analysis

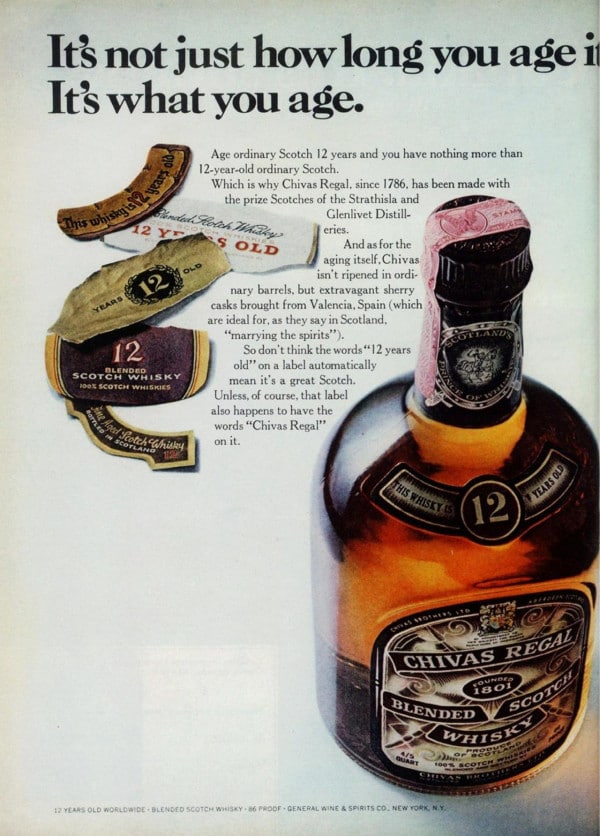

Of course, if you HAVE interesting and relevant facts on your side, there’s no reason NOT to use those in your ads.

Real differentiators are rare, but they can do wonders when properly applied.

And properly applied means used to support and reveal the personality of your brand, rather than as a substitute for a personality.

For instance, Chivas proudly proclaimed their Scotch as aged 12 years — a solid differentiator at the time.

So you’ll find that fact mentioned in most of their ads. But it’s rarely the lead.

See for yourself:

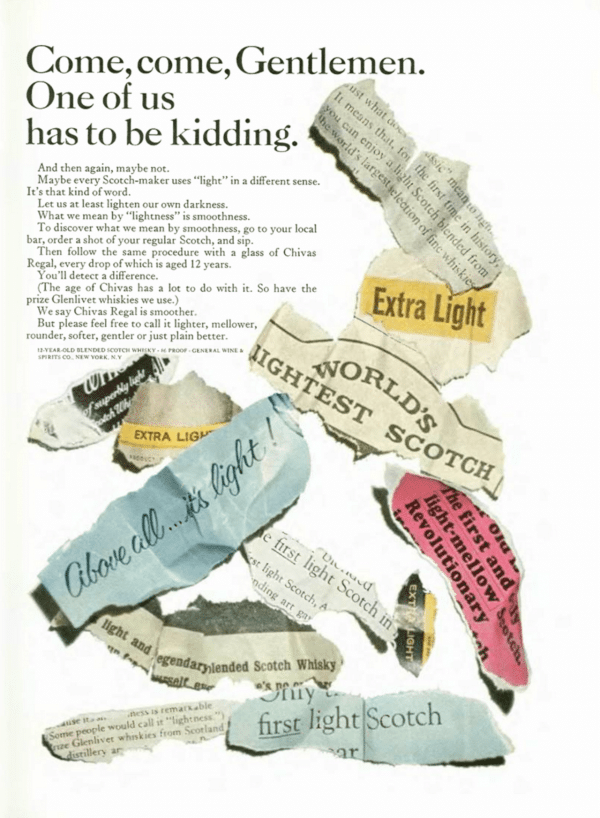

Note how DDB reframed aging to mean smooth and smooth to mean what people really want when they think they want “light”

That’s excellent copy based on sound strategy right from the brief — remember it was the “light” Cutty Sark and JB Rare cutting into sales?

But beyond that, there’s the matter of personality and attitude.

The attitude of “you’ll absolutely taste the difference — there are no bargains in scotches — and if you can’t taste the difference, we’d rather you saved your money” comes through first. The Aged 12 Year fact only serves to substantiate that attitude.

Of course, DDB weren’t above making the age of Chivas the prime point of the ad, but even then, personality — playful and confident — took center stage.

And here’s an extra tip: you know your ads are working when the competition feels compelled to respond to them.

So when other whiskey’s started in on the “Aged X years” bandwagon, DDB was ready:

Lesson #4: Creativity levels the playing field

Bernbach’s newer agency attracted challenger clients by selling the idea that “small companies…can’t afford to run just competent advertising” because “the big guys have competent advertising, too, and a hundred pages to your one.”

Bernbach sold clients on the giant-killing power of “memorability and originality” when pit against research-tested messaging.

He believed every ad needed to be “based on something worth saying,” which was then paired with visually striking imagery and a story that would emotionally connect the reader to the product.

The Chivas campaign is a perfect example of this style, even if Seagrams was hardly budget constrained when they hired DDB. But even if Seagrams was a giant, Chivas was a smaller player in the Scotch market at the launch of the campaign.

When DDB took over the Chivas account in 1962, US sales amounted to 135,000 cases annually. By 1979 Chivas was selling 1.125 Million cases per year in the US alone, making it the 5th most popular whisky in the country.

Sure, Seagrams had the ad budget for great ad placement in popular magazines. But great ad placement doesn’t actually ensure that your ads are seen, let alone read.

It only ensures that your ads can be seen. Creativity ensures that the ads are consciously noticed and then read.

And that’s why creativity is how smaller companies level the playing field against larger, better-funded companies.

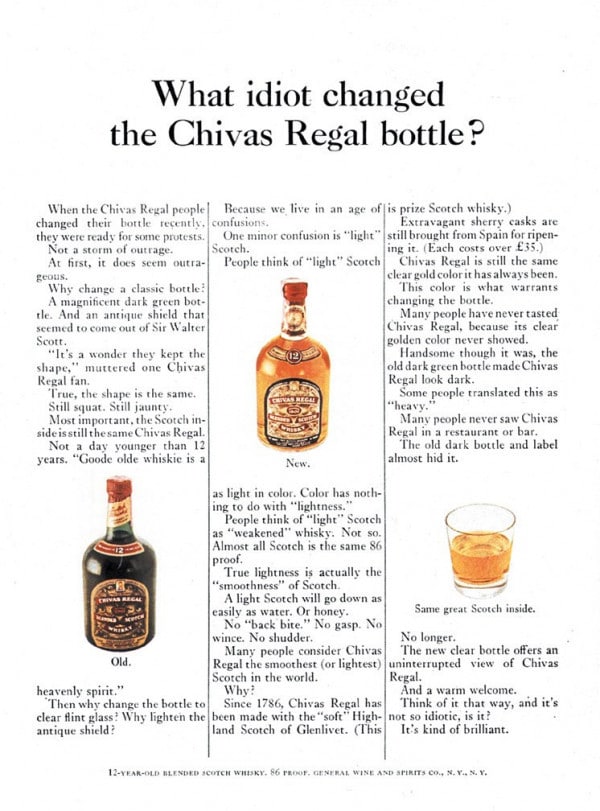

Bonus Strategy – Lamp-shading

I saved the very first ad in this campaign for last, because it perfectly illustrates the technique of lamp-shading. Here’s the ad, followed by the explanation:

If you’ve never heard of “lamp-shading, I’ll let TV Tropes explain it:

“[Lampshading] is the writers’ trick of dealing with any element of the story that threatens the audience’s Willing Suspension of Disbelief… by calling attention to it and simply moving on.”

In other words, don’t try to slip it past and hope no one notices or no one complains — highlight it.

With Chivas, they knew their established customers would likely think the repackaging was a bad move. So they owned it. They called it out, exactly like their customers would in their own heads.

And then they addressed and dismissed the change, while also tackling the “light scotch” challenge from the brief.

Remember the lesson on trust between client and ad consultant?

Ask yourself how much trust it would have taken for the owner of the company to run this ad?

And that’s why trust comes before creative and messaging strategy.

Looking for an ad consultant you can trust? I’d be happy to discuss it with you — preferably over a glass of scotch!

P.S. If you’re here from The Whisky Tribe, I hope Lesson #3 especially resonated with you. Personality trumps analysis, or you wouldn’t be here right now, right?

- Are You Paying for Too Much for the Wrong Keywords? - July 15, 2024

- Dominate Your Market Like Rolex — 4 Powerful Branding Lessons - July 3, 2024

- Military-Grade Persuasion for Your Branding - June 25, 2024