Martha had a great idea. Xavier had a bigger dream. Roger knew what to call them. The story of the Cabbage Patch Kids will surprise you.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Blubrry | RSS | More

Dave Young:

Hey, welcome back to another edition of The Empire Builders Podcast. Dave Young here, alongside Stephen Semple. We’re talking about empires being built, and people building fortunes and all these, I assume, serious business topics. Until Stephen whispers in my ear just before we start that we’re going to talk about Cabbage Patch Kids.

Stephen Semple:

That’s right.

Dave Young:

I feel like this happened before my siblings and little sisters… Between the time that I had sisters that would have had Cabbage Patch Kids or children that would have had Cabbage Patch Kids, because I think the whole thing was done by the time I had kids.

Stephen Semple:

You missed it?

Dave Young:

It happened in that liminal space between being a brother with sisters who had Cabbage Patch Kids or being a dad. It was a big, big thing, and then it wasn’t.

Stephen Semple:

You just missed it is what you’re telling me.

Dave Young:

Yeah. When did they start?

Stephen Semple:

When they got really big was in the ’80s. That’s when they were massive.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

There were three years there where they set every toy sale record known to mankind. They sold over 130 million units.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

They’re still around today, they’re just not a really huge, massive thing. They’re actually one of the longest-running doll lines in the United States.

Dave Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

But yeah, there was a period there where they were like holy smokes, just crazy, crazy, crazy big.

Dave Young:

Just the fact that I know about them. I was a dumb kid in his 20s with no reason to know about them in the ’80s. But I did. They were a cultural phenomenon.

Stephen Semple:

They were. I remember seeing on television, you would see shots of lineups at toy stores, and people going nuts trying to buy these things. It was really, really, really crazy.

Dave Young:

Cultural references, the Tonight Show, and all kinds of things. They were everywhere.

Stephen Semple:

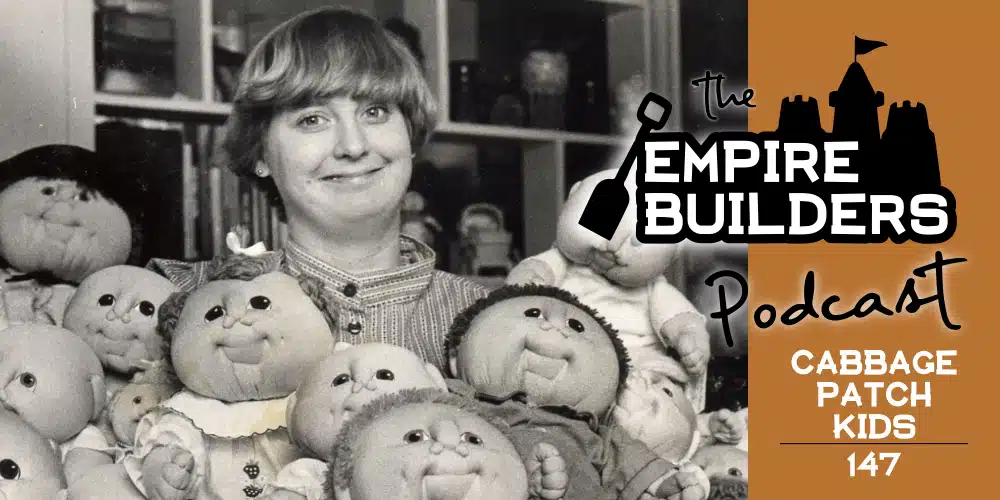

Oh, yeah. They really were. They were created by a lady by the name of Martha Nelson Thomas. She was an art student. She went to the Louisville School of Art, she graduated there in ’71. She wanted to create dolls that would touch people. They were handmade and they were each different. She was an artist. In art school, one of the things she did was this whole idea of what’s called soft sculpture, which is about using sewing techniques and things along those lines, to create shapes, soft items, pillows, and things along those lines.

If we think back to the ’60s and ’70s, dolls were all mass-produced from plastic. In the ’70s, we started getting this folk art movement rising and this return to more organic forms. What she started to do was create these dolls where the features were created by the stitching. This created something soft and cuddly. She called them doll babies. When she was selling them, she included an adoption certificate, named each baby, and wrote down some of the characteristics. Things that the baby liked and disliked, and things along those lines.

Dave Young:

Right.

Stephen Semple:

It gave each one a unique look and a unique character. She starts to display these dolls at crafts fairs in the areas, and the dolls sell pretty well in local markets. Along comes Xavier Roberts, who sees the dolls. He’s working in a gift shop, and he sees these dolls, and he convinces her to let him sell some of the dolls. It’s this handshake deal where he’s going to resell them.

He starts selling them at the gift shop and they sell like wildfire. He invites her to his local craft fair and she notices that he’s selling them in his stores for less than she’s selling them at the craft fair, and she doesn’t like the lower price. She sends a letter to him, basically stopping the relationship, saying, “We’re not going to work together any longer,” and to cease and desist with his sales practices. He replies that he never agreed to the price and he will continue with her or someone else.

He had also been an art student. He had a pretty good understanding of textiles because his mom worked in a textile factory, and had taught him how to quilt and things along those lines. He decides to make his own version of the dolls. He tweaks it a little bit and he names them Little People. He signs every doll like it’s a piece of art.

Dave Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

It’s 1979, and Martha’s making a modest living selling her babies, and she discovers that he’s selling his version because a buyer makes a comment. They’re going, “Oh, these are just like Little People.”

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Oh yeah, I just like it.

Dave Young:

I’m sure, like most industries, it’s a small world. The toy makers know who all the other toy makers are.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. The jig is up and she’s devastated.

Dave Young:

Oh, yeah.

Stephen Semple:

He also did a number of things like hers. He also did a birth certificate, he had adoption papers. He claims he’s the father, and he has this idea that the babies are not for sale, you can only adopt them for a fee.

Dave Young:

Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. Wait, wait, wait. He claims he’s the father of all these?

Stephen Semple:

He does initially.

Dave Young:

Okay, that’s it. That’s a different topic for another time, but somebody else’s podcast can cover that aspect of this.

Stephen Semple:

He does that. But then he pivots because he wants to create this immersive world. There needs to be this story. He creates the idea that babies come from cabbage patches. Now he has this concept of them coming from cabbage patches. He decides to create an attraction. He’s really inspired by the immersive experiences at places like Disney creates.

He finds this abandoned doctor’s clinic in Cleveland, Georgia, and he refurbishes it. He created Babyland, and it’s the birthplace of the dolls. People can come in to adopt a doll. He doesn’t have a lot of startup capital, so he goes to the bank saying he needs capital to build a hospital where baby dolls are born out of cabbages.

Dave Young:

I’ll bet that was the topic during the coffee break at the bank.

Stephen Semple:

But you know, he’s a pretty convincing guy and he actually gets a loan, and puts everything into it. In the fall of 1978, he opens to the public. They have incubators and the whole thing. The staff are called nurses and doctors. The cabbages are injected with amoxicillin, which dilates and reveals a baby within. It’s huge. In less than a year, he has a staff of 56 people. It’s a huge tourist draw. In fact, what’s really interesting, it’s still around today. It’s still around today. People would go home with a toy and a story.

Really what we have is the same dolls being sold in a new way. We have the same dolls that Martha had, but being sold now in this new way, through this little hospital.

Dave Young:

Right.

Stephen Semple:

Martha goes and gets legal representation and starts action against-

Dave Young:

Well, yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Surprise, against Xavier here. Surprise, surprise. But in the meantime, he’s this huge success in Georgia, has this mass appeal and he wants to scale up. Roger Schlaifer approached him to do advertising for them, so they created a logo. He suggests doubling down on the mythology. But what he realizes is they need to change the name because the name’s not unique, because Fisher Price owns the name Little People. He suggests Cabbage Patch Kids.

Now, Calico comes along and wants to do a deal with them. But here’s one of the challenges. How do you mass produce them and make them unique? Meanwhile, we have this lawsuit going on for Martha, where she wants acknowledgment that it’s her idea. While he’s fighting that off, he’s looking to do this manufacturing.

What he decided to do was make the faces out of vinyl, but what they would do was six molds, change the eye color, change the skin tone and the hair to create variability, different clothes, et cetera.

Dave Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

Which makes each doll different, but now mass-produced. Calico orders two million in a factory in Hong Kong. What’s interesting is Calico got into this because, at the time, the toy industry was technology crazy but Calico was getting concerned that that might be coming to an end.

The thing that’s interesting, when you look at Cabbage Patch Kids, is that they’re kind of ugly but people still wanted to have them.

Dave Young:

Yeah. I wasn’t going to point that out.

Stephen Semple:

But, there’s this thing, the uglier something gets, the more our brain flips it to cute. The more we need to rescue it. This has actually been studied. There’s been a bunch of studies around this whole capturing of imperfections, and imperfections making things kind of more adorable.

Now the court rules in favor of Xavier. Remember, we’ve got this court case going on between Xavier and Martha. He wins round one. Now, she doesn’t give up.

Dave Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

They’re now building a second trial and this one’s more around some ideas on advertising. But he pushes ahead and launches the new kids. In 1983, they released to the nation two million Cabbage Patch Kids, nationwide. There’s a mad rush.

Dave Young:

Wow.

Stephen Semple:

Demand like never been seen before. It sells out before Christmas. Stores are selling out in hours. They’ve now got plants working 24 hours a day, they’re creating 200,000 of these things a week. They’re air freighting them. This was a bit of an accident, this was never planned by Calico, part of the appeal is they’re hard to get.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

And the craze is chaos. The reason why you and I remember it is we would see on television, news segments where there are police barricades and people fighting to get their hands on these damn dolls.

Dave Young:

Here’s the funny thing. I remember that. But we talk about scarcity. We talk about it with clients, we talk about it with students and we talk about ways to create scarcity or the appearance of it. Limited time offers, limited quantity, and lots of different things you can do. Here they get scarcity by right of scarcity. They actually were scarce. It’s like this is lesson one of scarcity.

Stephen Semple:

What I always wonder about things like that, is if they knew, somebody told them ahead of time, “There’s a demand for 400 million of these,” would they have made 400 million and then released them? Companies are so afraid of scarcity, yet scarcity is really, really valuable. We see this a lot in certain clothing brands. There’s a number of clothing brands out there that have done great jobs of creating really and truly limited edition things, limited edition releases that sell out like wildfire, and end up becoming collectible and hugely valuable, and all this other stuff, simply because of the scarcity that is around it.

Dave Young:

Sure. It’s real, and I think in their case, you probably wouldn’t do it. I think we have a tendency to create some kind of offer that feels scarce before we create actual scarcity. It’s like saying, “It’s a limited edition?” Well, what’s it limited to? “Well, it’s limited to however many we can sell.”

Stephen Semple:

Exactly, yeah. We’ll stop making it when they stop selling.

Dave Young:

It reminds me of the old, I think it’s a Yogi Berra line, but, “This place was really popular until everybody started coming here.” Cabbage Patch Kids were really popular until everybody had one.

Stephen Semple:

That’s true.

Dave Young:

There’s a certain truth to that. They’re immensely popular when you can’t get your hands on one.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. The whole limited edition thing is kind of interesting, too. I remember one time, because of course, every university student had a drinking game around The Antique Roadshow somehow. I remember watching it one time and somebody talking about … This person brought in this item. He said, “Well, you know it would be really valuable if it wasn’t the collector’s edition.” I was like, “What?” He said, “Yeah because the problem is everyone holds onto the collector’s edition and throws the other ones out. The ones that are really valuable are the ones that are not the collector’s edition.”

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Because there are fewer of them around.

Coming back to the Cabbage Patch Kids, Xavier’s now worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Popularity between 1984 and ’85 is just off the charts, there’s several billion dollars worth of Cabbage Patch Kids stuff sold. Especially when you take into account all the licensing. There were 2000 licensing deals done in 1985.

Dave Young:

Wow.

Stephen Semple:

In terms of being able to put Cabbage Patch logos on other things. But Martha gets a breakthrough because they go to court over this whole idea of reverse confusion. The idea of reverse confusion is somebody thinking that the Cabbage Patch doll was the original, rather than hers being the original. She ends up settling out of court for an undisclosed amount of money. Xavier also had to admit that the inspiration came from Martha.

When you read about Martha, at the end of the day, she didn’t become wealthy off of it. But you know what, she was an artist, she put her kids through college, and she had a house. She managed to get a decent financial settlement out of all of this.

Dave Young:

I was going to say, I hoped she was at least happy for the rest of her life. I don’t know, she might still be around.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. I saw an interview with a friend of hers when I was researching this and she really talked about how she was quite content and financially comfortable for the rest of her life so Martha has seemed to do well.

But here, coming back to scarcity, here’s where things started to go wrong for Cabbage Patch Kids. Calico, because now the technology craze had started to come to an end and Calico was heavy into that space, Calico started to have financial problems. What they needed to do was make more Cabbage Patch Kids to overcome their financial problem. Cabbage Patch Kids sales were starting to just slow a little, tiny bit and they flooded the market.

Dave Young:

There goes scarcity.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, there goes scarcity. It went the other way and all of a sudden, Cabbage Patch Kids just suddenly went from being this really hot item to being completely unpopular. Calico goes bankrupt and the license is sold to Hasbro. The funny thing is, that Babyland in Cleveland, Georgia is still around.

But there are a couple of things that I thought were really neat when I was reading about this, that I didn’t know about. That is in the early days of the Cabbage Patch Kids was this really super immersive experience that he created. Literally, when you went in, there were people dressed as nurses who would swaddle up the baby and bring the baby out for you to take a look at. The adoption certificates, and the names. They even had this whole thing they had created where they would do this little phony injection thing, and the cabbage would open up and there’d be this baby there. It sounds so insane.

Dave Young:

It sounds really creepy.

Stephen Semple:

It does sound really creepy. But what we know is, when you really create this big experience, when you go heavy at it, that’s actually when these things work.

Dave Young:

Yeah, it’s an amazing story.

Stephen Semple:

It created this massive phenomenon. And then, the scarcity just blew it into a whole new realm, and then it was the elimination of the scarcity and the market saturation that blew the whole thing up. In the wrong way.

Dave Young:

Here’s my hunch. The clinic in Cleveland, Georgia helped them create the stories. It helped them create the mythology of it. There can’t be more than a small percentage of customers that ever went there.

Stephen Semple:

Yes, correct.

Dave Young:

I just looked on Google Maps, it’s the middle of nowhere.

Stephen Semple:

It is in the middle of nowhere.

Dave Young:

It’s this tiny little town. It’s an hour, an hour-and-a-half from downtown Atlanta.

Stephen Semple:

We’re in Atlanta next week, we’re not going there.

Dave Young:

Oh, I was thinking we should get our photo. I’m interested in it, almost for the same reason, I’d be interested in a haunted house.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, there you are. There you are.

Dave Young:

Man, I think the lesson of scarcity and the lesson of having a story that goes along, almost an individual story with a mass-produced item. That’s hard to do. You’ve got to hand it to them for that.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, because they each had a name, they had likes and dislikes, which was the thing Martha came up with that he built upon. He built upon that and then took the story deeper. They did a couple of things that no one had done before. They were ugly dolls. They were individuals. Everybody else in the doll industry was mass-produced, identical, and beautiful. They were doing this individual, unattractive, weird story behind it. That’s what captured people’s imagination.

Dave Young:

The right scarcity at the right time.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. Hats off to Martha, hats off to Xavier. It’s too bad they weren’t able to find a way to do it together. That’s the only part that’s sad in the whole story.

Dave Young:

And on my part, bullet dodged not having them in my house.

Stephen Semple:

I hear you, man. I hear you.

Dave Young:

They were too popular by the time my kids needed one. “You can’t, everybody’s got one of those. You don’t need one.”

Well, thanks for sharing the Cabbage Patch Kids story on The Empire Builders Podcast, Stephen.

Stephen Semple:

All right. Thanks, David.

Dave Young:

Thanks for listening to the podcast. Please share us, subscribe on your favorite podcast app, and leave us a big, fat, juicy five-star rating and review. If you have any questions about this or any other podcast episode, email questions@theempirebuilderspodcast.com.

- Tapping Into the Zeitgeist: Monopoly’s Origin Story - December 17, 2025

- From Mars Men Mediocrity to Sour Patch Success - December 10, 2025

- The Hidden Psychology Behind Cabela’s Success - November 28, 2025