How to take over the world the same way De Beers did it, any business can follow this simple rinse-and-repeat formula.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Blubrry | RSS | More

Dave Young:

Well, here on The Empire Builders Podcast, we share stories about all kinds of businesses. And I grew up in Nebraska. So when Steve said we’re going to talk about De Beers, I figured Bud Light, Coors Light, but he’s Canadian. So maybe it’s Labatt’s Blue. We drank some of that in college, but it turns out we’re not even talking about beer when we talk about De Beers.

Steve:

No, not those De Beers. No.

Dave Young:

This is the diamond De Beers.

Steve:

This is the diamond De Beers. Yeah. It’s a really interesting story because they really invented the idea of diamonds for engagement. We forget that there was a time when diamond rings were not the standard for engagement. In the late 1920s, only 10% of engagement rings were diamonds. Only 10%. Where today, it’s 80. And they were the ones that really drove that. And De Beers has got a really interesting playbook. I’ll lay out the six things in their playbook, and we’re going to study some because one is to control supply. And they had an interesting way that they controlled supply. And the reason why they wanted to control supply is if you grow demand then you get most of that demand. And they also believed in limiting distribution. Now the supply control and the distribution, that’s since been shattered. But the whole idea is to create scarcity.

And there’s an interesting thing to that. But the big thing is, what they wanted to do was also create demand. So they were facing a similar challenge to another podcast we did, which was Michelin, where I need to create more demand for my product. But what they also wanted to do was link spending to success. And they wanted to define the value and use price as a marketing strategy. So here’s what they did. Most businesses, when it comes to using price as a marketing strategy, what we find is that most lower price, right? Not De Beers. We’ll get to that a little bit later. So before World War II, there was the Depression, and De Beers was starting to sell diamonds. And they had this real fear of the risk of people selling their diamonds. And they wanted people to keep their diamonds because they didn’t want to have a flood of diamonds onto the marketplace.

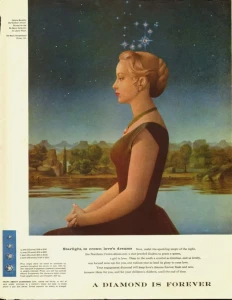

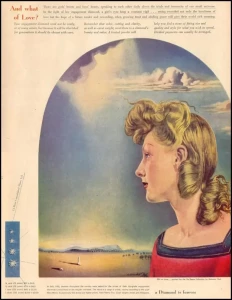

So their first advertising campaign was really developed around this idea of encouraging people to keep their diamonds. So it really wasn’t about initially selling them more diamonds. It was about keeping the diamonds. Remember, limit supply. So they hired an ad agency, N.W. Ayer and Sons. And one of the people there, Mary Frances Gerety in 1948, coined the term “A diamond is forever.”

Dave Young:

Okay. 1948.

Steve:

So that’s where that started. So there’s this halo effect, right? When you attach your product to other things that are really famous or valuable. If I take something’s valuable, and I put something next to it that’s valuable. It’s perceived to be valuable, right? Well, what they did was they ran magazine ads with paintings by famous artists. Right? So those diamonds are also a work of art, and diamonds are also valuable. And these were famous artists like Picasso.

And we’ll have some examples of those in the show notes, but it’s also really funny. When we go back, they were one of the first to do product placement in a movie. In 1939, Gone with the Wind. What does Scarlett O’Hara ask for from Rhett? “I want a big old diamond, big enough to choke a horse,” right? And at that time, remember, only 10% of engagement rings were diamonds. That was product placement. Now-

Dave Young:

That’s cool.

Steve:

So in 1939, it’s 10%. 1948, they start running the “Diamond is forever” campaign. And they start doing the magazine ads with the famous painters. By 1950, one-third of all engagement rings were now diamond rings. By the 1990s, this number became 80%. So this huge growth… Here’s where it gets really interesting. This campaign worked so well that they decided to do it in Japan. So in 1967 in Japan, hardly any engagement rings were diamonds. They took the very same campaign that they ran in the United States. And one could argue, “Oh, but Japan’s different, right?” How many times, Dave, have we heard clients say, “Well, that worked in Texas. That’s really not going to work in Oklahoma.” Right? They took a campaign that worked in the United States, and they took it to Japan. And in 1967, hardly any engagement rings were diamonds. And by the mid-1980s, 70% of engagement rings were diamonds.

Dave Young:

All right. So Japanese people are buying diamonds now.

Steve:

Based upon a campaign that worked in the United States. So then they said, “Let’s go to China.” Did they create a campaign specifically for the Chinese market? No. They ran the same campaign again, the one that they ran in the United States and the one that ran in Japan. And they ran it in China. “Diamond is forever.” Same result, because people are people. Yeah. In a couple of decades, half of the engagement rings in China are now diamonds.

Dave Young:

Amazing.

Steve:

And back to this pricing thing we said we’d come back to. As a pricing strategy, most businesses would go cheaper. Right? Well, there are three classes of goods — economists talk about that. There are elastic goods and inelastic goods. And so elastic demand means if I lower the price then demand goes up. Inelastic means I change the price, and demand doesn’t change. And then there’s what’s called Veblen goods.

You can look this up. Economists talk about that. And it is ones where you increase the price, and you actually increase the demand. There are actually products and services out there that when you increase the price, you increase demand. And there are some really interesting studies of bread makers that have been sold through William Sonoma, where they’ve had this happen. Where they’ve increased the price and demand has gone up. Don’t automatically assume by lowering prices that I increase demand. Demand may go up if it’s elastic. Demand may remain the same if it’s inelastic, or demand may go down if it’s a Veblen good, V-E-B-L-E-N.

And it’s named after the economist who actually uncovered this idea. And he was the economist who also coined the term conspicuous consumption. And here’s the weird thing. Studies just show men are more connected to diamonds than women, actually. Studies are showing that men would sacrifice more than a woman in order to buy a diamond. Although men joke it’s the woman who wants the big rock, but deep down inside, it’s the men. It’s a sign of success. And women care less about this than men. If you did focus groups on this, it would be easy to come to the conclusion, if you listen to the women, that none of this is important. But it’s also why they linked it to salary.

Dave Young:

Yeah. In a society where none of us want to talk about how much we make, we have these things that show how much we make.

Steve:

Yeah, absolutely. And diamonds became very, very much that way. It was Thorstein Veblen who basically coined the term. And he’s the economist who coined the term “conspicuous consumption,” but pricing strategies have a couple of different directions that they can go. But to me, the most interesting lesson in all of this that anybody can take away is, it would be really easy to say, “That worked in the United States. It won’t work in Japan.” Well, it worked in Japan. “That worked in the United States and Japan. Won’t work in China because China’s got all this other stuff.” Well, it worked in China. And the empires we’ve studied is what they’ve done is they take what’s working, and they multiply it. Right? Starbucks got its idea from Italy. And everybody said, “Well, that worked in Italy. Won’t work in the United States.” Worked in the United States, and then they multiplied it. Right? Go outside of your area, and see what others are doing. And with globalization, this is becoming easier to see. But don’t go, “Oh, that worked there. That won’t work here.” And then also, as you’re expanding your business, if you want to grow, the best way to expand is, to take what’s working in your town and move it down to the next town.

Dave Young:

I’ve had clients where we know that we’ve grown them to the point where they’re the dominant retailer or service provider in their town. And they’re struggling with that. They’re telling us, “How are we going to get more people?” It’s like, “Well, you’re already at 40% of the market share, and you can’t really grow it past that. So yeah, you got to go to a new town.”

Steve:

And it’s even a safer thing to do than to open a new business. Because anytime you open a new business or do the death killer, line extension, you run all of these risks, and don’t get caught in this, “Well, you know that worked in Texas, won’t work in Oklahoma.” No, it’ll work in Oklahoma. So that’s the path to building an empire find what works and repeat it.

Dave Young:

Yeah. Great lesson. And I think next time you and I, we’ve been recording these over Zoom because pandemic, et cetera, et cetera. And next time we get together, we need to have De Beers.

Steve:

Yeah, a couple De Beers. Cold De Beers.

Dave Young:

Cold de Beers.

Steve:

All right. Thanks, David.

Dave Young: Thank you. Thanks for listening to the podcast. Please share us. Subscribe on your favorite podcast app, and leave us a big fat juicy five-star rating and review at Apple Podcast. And if you’d like to schedule your own 90-minute Empire Building session, you can do it at empirebuildingprogram.com.

- Folgers – The Best Part of Waking Up - February 21, 2026

- Red Bull’s Branding Duality - February 12, 2026

- How Alienware Spotted Unidentified Flying Opportunities - February 4, 2026