“Emotional campaigns are 30% more likely than rational campaigns to show large profit effects’ and ‘Fame campaigns, those that set out to achieve fame, (awareness, buzz, talk-ability) are 80% more likely than rational campaigns to achieve large profits.”

— Binet & Field, The Long and Short of It

After reading that, does it surprise you that a whole lotta biz owners are eager to get their hands on some of that sweet, sweet “large profit effects” via emotional ad campaigns?

After reading that, does it surprise you that a whole lotta biz owners are eager to get their hands on some of that sweet, sweet “large profit effects” via emotional ad campaigns?

Heck, no! You probably want some of those “large profit effects” yourself, right?

The problem is “emotional” doesn’t mean what you think it means — at least not within the context of advertising effectiveness research.

Emotions in the Audience, Not (Necessarily) On the Screen

First, an emotional ad is NOT an ad showcasing emotions “on screen,” aka within the ad itself; it’s an ad that causes an emotional response in the audience.

What Emotions, Exactly?

Second, “emotion” can mean any number of things, to include engagement, valence, physiological reactions, and emotional priming.

In other words, if you think of emotional advertising in terms of happy, sad, or angry, you’re missing the boat.

Mild curiosity and low-key surprise “count” as emotional reactions; laughter or tears are not required to check that box.

Not All Reason-Why Messaging is Direct Response

Third, and perhaps most importantly, the quoted research isn’t comparing branding campaigns that employ emotion against branding campaigns that employ rational, reasons-why approaches.

In the case of Binet and Field, rational means “short term sales activation,” and emotional means “long-term branding.”

So what’s the data on reason-why-centric branding vs. overtly emotional branding?

Well, this is where it gets dicey, in my opinion.

Because a so-called rational message is entirely capable of creating an emotional response in the audience.

“It’s a girl, weighing 9 pounds, 3 ounces” is a simple statement conveying entirely rational information.

But you’d be hard-pressed to say it doesn’t evoke a profoundly emotional reaction from the newly-minted parents.

Similarly, if you committed to an “emotional campaign” in an effort to save your business, the rational data that sales are up 50% would carry a significant emotional impact as well.

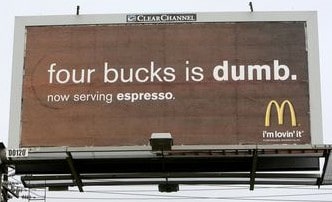

Let me show you some ads justly famous for creating “large profit effects” and building enormous brand value that no one would call “emotional” in the regular sense of the word (but that would undoubtedly be classified as such by advertising researchers):

Emotion Isn’t The Goal

So what’s my point with all this?

Emotion isn’t the goal.

Preferential purchasing behavior is the goal.

And to that end, getting customers to think of you first and feel the best about you is the goal.

Just note that “feeling the best about you” is more like a “gut feeling” that you’re a better choice than the next guy – an intuitive assessment of your competency, honesty, and ability to solve the customer’s problem —rather than some deeply felt “love” for your brand.

Yes, emotion can be a powerful tool for advertisers.

As one copywriter has put it, emotion is the ink memories are written in.

But you don’t want people remembering the ink — you want them to recall the message.

So while emotions help form associations and strengthen recall, there still has to be something meaningful to associate and something relevant to recall when a customer’s moment of need arises.

Look back at those not-so-emotional-but-still-hugely-profitable ads, and you’ll find that the low-key emotions they do generate are aimed squarely at meaningful and relevant messaging.

Put another way, emotion is the engine, but meaning and relevance are the transmission.

Are your “emotional” ads going somewhere, or are they just revving the engine?

P.S. If your mind naturally focused on “Fame” rather than emotion when reading the Binet and Field’s quote above, check out my post on how to craft campaigns capable of achieving Fame

- Are You Paying for Too Much for the Wrong Keywords? - July 15, 2024

- Dominate Your Market Like Rolex — 4 Powerful Branding Lessons - July 3, 2024

- Military-Grade Persuasion for Your Branding - June 25, 2024