What Henry Ford learned from a slaughterhouse and how it changed the world.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Blubrry | RSS | More

Dave Young:

Stephen, I’m looking at the show notes, and today it says Ford and the word model, and I’m thinking of the Ford modeling company. Well, this could be kind of fun and exciting.

Stephen Semple:

I kind of wish now. I think I’m going to disappoint you. You are talking about a Lizzie, but it happens to be Tin Lizzie.

Dave Young:

The Model T.

Stephen Semple:

The Model T Ford. That’s what we’re going to go back and talk about, but before I get started, I wanted to read something to you. I’m not sure whether you read this week’s Monday Morning Memo. You know, Roy does a memo every Monday. Roy’s consistency on the memo, it’s kind of what really inspired me when I approached you for doing this podcast of really wanting to produce something every week and do that consistently. Now, I had a long time to catch up to him; he’s been doing it for like 30 years or some crazy number, but there was a piece I came across in the Monday Morning Memo. I want to read it because it captures the real essence of what we’re doing in this podcast and also specifically why we’re going to talk about the Model T Ford today.

Dave Young:

Let me just put a preface on this. We record these things pretty far in advance sometimes, and I want to make sure that if somebody wants to go back and read this particular Monday Morning Memo, we’re talking about the December 20th, 2021 Monday Morning Memo.

Stephen Semple:

Thank you for that, Dave. So David, here’s what Roy wrote, “But what makes them wonderful? Wonderful things were touched by someone who knew the secret of wonder and how to capture it. When you know how to capture wonder, you carry it on your head, your heart, and your hands. You glitter when you walk. Isaac Newton knew how to capture wonder, and he passed the secrets forward in just 14 words. Countless millions have read those words and assumed Newton was talking about himself. He was not. Newton was giving you his most precious advice. He was telling you how to capture wonder. He was telling you how to glitter when you walk.

In 1675 Newton wrote, “I have seen further. It is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Isaac Newton stood on the shoulders of Galileo, Kepler, and Copernicus in astronomy. Huygens, Euclid, Henry Briggs, Isaac Barrow and math, Kepler and Descartes in optics, Plato, Aristotle in philosophy. Newton combined the insights of these men and made them uniquely his own.

Choose your giants. Stand on their shoulders. Repurpose the proven. Vincent Van Gogh stood on the shoulders of Monticelli and Hiroshige long after they were dead. They taught him how to paint. He studied their paintings, captured their wonder, and made it his own. Johnny Depp stood on the shoulders of Pepe Le Pew, the cartoon skunk, and Keith Richards, The Rolling Stones. They taught him how to capture our Captain Jack Sparrow. Depp studied their mannerisms, captured their wonder, and made it uniquely his own.

Roy says he stands on the shoulders of John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, Robert Frost, Tolkien, Paul Harvey, and Robinson. They taught him how to write. In fact, he says he borrowed the smokeless of burning decay from Robert Frost and “glitter when you walk” from Robinson. Here’s a reason why I share that. That is what we do here.

Dave Young:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Stephen Semple:

We stand on the shoulders of giants. Roy is an amazing writer, and he stands on the shoulders of those writers. My gift that I bring is being able to look at these business models and say, man, this is what you can use and learn from in the past and apply it today to drive you forward. Stand on the shoulders of giants. That’s what we do in this podcast.

Dave Young:

That’s what we’re helping the listener do. If you’re trying to build a business and you’re not sure which giants’ shoulders to stand on. Well, we’re talking about those giants every week.

Stephen Semple:

We talk about them every week. We talk about self-made billionaires like Sarah Blakely and Tony Hsieh. We talk about companies like Ford. We talk about companies like Intel, but the things that they did that turned them into giants. And today, we’re going to be talking about a company and an innovation that probably changed the world like no one has before. It’s really quite remarkable, and even today, Ford is still a monster in the car business. They’re the fifth largest car maker in the world. They make over four million cars a year, to put that in perspective. That’s 11,000 cars a day. That’s 450 every hour, every seven to eight minutes, every eight seconds. There’s a car being made by Ford. But here’s a staggering fact. In 1925, they were making 10,000 Model Ts a day. That’s almost as many cars as they make today, and that was all domestic consumption, and in 1925, there were only 115 million people in the United States. It was a third of the population of what it is today. The advent of the Model T Ford changed the world.

Dave Young:

Yeah, you know, one of the things I think about when I think of standing on the shoulders of giants and especially things like that when you talk about the sheer numbers, to me, one of the biggest benefits is these giants think bigger thoughts. When I think about somebody like Ford and putting out that many cars a day, that’s just a bigger thought than I usually come up with in my own head. You stand outside the Hoover Dam near Las Vegas, and you think, wow, somebody thought a huge thought when they thought, “We’ll just dam this entire canyon.” I mean, it’s just-

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, absolutely.

Dave Young:

… you think bigger thoughts, and it just makes you have bigger plans.

Stephen Semple:

Well, and let’s put in perspective how big this went. In 1900, there were 4192 cars built in the United States. Now here’s some interesting thing. 935 are gas. 1575 were electric, and guess what? 1681 were steam-powered, but by 1908, eight years later, and this is the year that the Model T was introduced, there were 2000 cars on the road, and there were 500 companies making automobiles.

Dave Young:

Hmm.

Stephen Semple:

By 1919, 6.7 million. By 1929, 27 million cars.

Dave Young:

Mm.

Stephen Semple:

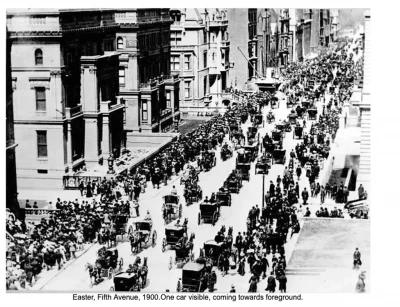

Went from 4000 to 27 million in basically 20 years, and over this time, there were 15 million Model T Fords sold. More than half of the cars on the road were Model T Fords. And look, the Model T remained the best-selling car of all time until the Volkswagen Beetle, which you can listen to in episode 21, came along. So it was this massive change, and in the show notes, I’ve got two pictures that I’ve put up, and one is a photograph taken on Fifth Avenue at Easter and Fifth Avenue in 1900. And when you look at that picture, it is all horse-drawn carriages.

Went from 4000 to 27 million in basically 20 years, and over this time, there were 15 million Model T Fords sold. More than half of the cars on the road were Model T Fords. And look, the Model T remained the best-selling car of all time until the Volkswagen Beetle, which you can listen to in episode 21, came along. So it was this massive change, and in the show notes, I’ve got two pictures that I’ve put up, and one is a photograph taken on Fifth Avenue at Easter and Fifth Avenue in 1900. And when you look at that picture, it is all horse-drawn carriages.

Dave Young:

Mm.

Stephen Semple:

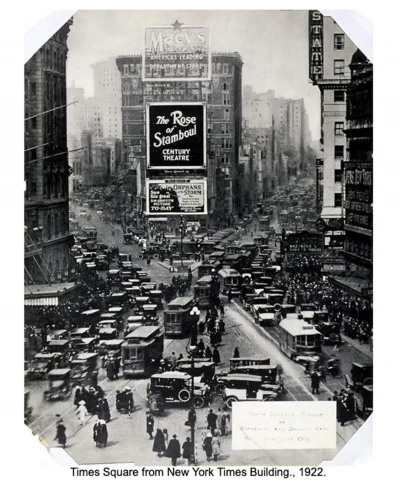

There is one car. One car to be found. And then there’s another picture that I found of Times Square taken in 1922; there’s not a horse to be found. It is all cars. Think about that staggering change.

Dave Young:

We think that the internet brought us a staggering change, and honestly, I have to think that those 20 years between going from horses to all cars had to have been a much bigger change in just the way everybody lived. I don’t think about the way I lived being that much difference between today and before the internet, other than I spent a lot more time in front of an electronic device.

We think that the internet brought us a staggering change, and honestly, I have to think that those 20 years between going from horses to all cars had to have been a much bigger change in just the way everybody lived. I don’t think about the way I lived being that much difference between today and before the internet, other than I spent a lot more time in front of an electronic device.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, it’s a massive change, so here’s what we’re going to talk about today is how did Ford create this change because the thing that he brought was this idea of the moving assembly line, and it was more discovered than invented. Let’s talk about that.

Dave Young:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Stephen Semple:

So Ford was founded on June 16th, 1903, by Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan. But the first Model T was sold on October 1st, 1908, so basically, there were five years where they were making cars that were not Model T, and Ford did like everybody else; they were making expensive cars. They started off in 1903 making the Model A, and then they did the Model K, and then they did the Model S, and in 1907 they did their first six-cylinder model known as the Gentleman’s Roadster, and the Silent Cyclone, and these cars were all expensive. So for example, the Gentleman’s Roadster sold for $2,800. And to put in perspective, in 1908, the average wage was 22 cents an hour. A laborer would make between two to $400 a year. A competent account would make a couple grand. Cars were expensive and for the rich, and Ford knew that what he wanted to create was something that was for the common man because he was out seeking ideas. And the Model T, when it was first introduced, came out at $850 but by 1925 fell to $265. That would be the equivalent of $4,000 in today’s money. And the reason why we know he was out seeking a solution is– so they were making cars, and there’s already a bunch of things that they were doing. They had already created this whole idea of outsourcing parts. That idea was created by Oldsmobile, and Ford was doing it as well.

Also, this idea of standardized parts. Cadillac had already created that idea, so they’re already doing those things to create innovation. The next step was figuring out really how to bring it down, and Ford was very interested in automation. It’s well documented that in 1906, he went and he visited the 40-acre Sears warehouse, this huge warehouse that Sears had for handling mail orders.

Dave Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

So he had been investigating all of these things, but the interesting thing is the moving assembly line is the thing that made the difference, and the moving assembly line is the product comes to you. So there are kind of two conveyor belts. One brings in the car, the other brings in the parts, and the worker stays in place putting the pieces in. And Ford didn’t invent that. It was an employee of Ford’s. William “Pa” Klann. There are lots of people who’ve been given credit, but this is well documented in the Ford Museum. Here’s the brilliance, so we’re always talking about at the beginning of this, you’re seeking bigger ideas and bigger things, and Klann discovered this idea of the moving assembly line when he visited a slaughterhouse.

Dave Young:

Ah.

Stephen Semple:

So he visited a slaughterhouse in Chicago and what he noticed was how quickly a pig could be taken apart.

Dave Young:

So it was a moving disassembly line.

Stephen Semple:

It was a moving disassembly line. Exactly. A person would stand there, and they would do a very specific cut of meat. Move to the next person, and they’d do a very specific cut of meat. Move to the next person in a very efficient manner, they took a pig apart, and he went, “Why couldn’t you just do that in reverse?”

Dave Young:

So you didn’t need to have skilled butchers at every station. You needed to have somebody and teach them how to make the one cut that they were going to make.

Stephen Semple:

Teach them how to make the one cut they were going to make and that inspired him to go, “You know what? We could build cars that way and create that efficiency and that training,” and in fact, I’ll put this in the show notes, there’s an early YouTube video, that’s segments of a training video that was actually made in the 1920s for training people on how to put the cars together. William “Pa” saw this idea, and he reported the idea to Peter Barton, who was the head of Ford production, who at first was a little bit skeptical, but encouraged him to pursue the idea, and they began building Model Ts that way. And they eventually divided the process into 45 steps, and they could build a Model T from start to finish in 93 minutes.

Dave Young:

93 minutes.

Stephen Semple:

93 minutes.

Dave Young:

That’s just amazing, isn’t it?

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. And they were coming off the assembly line every 10 or 15 seconds, right? Boom. Boom. Boom. But start to finish 93.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

93 minutes. Now I’m sure you’ve heard this line. I wasn’t able to find out whether this line was ever actually said by Henry Ford, but it was attributed to him. Have you ever heard the line? “You can have it in any color as long as it’s black?”

Dave Young:

Yes. Yes.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, and a lot of people will say that, and that was sort of part of his pushback on customization and everything needed to be automated, but that’s actually not why that line was said. That line was said because when they first started making the Model T Ford, it wasn’t multiple colors. You could get it in green and get it black, get a bunch of different colors, but as they sped up the assembly line, they ran into a problem. And the problem was the paint was the bottleneck. It wouldn’t dry fast enough.

Dave Young:

Mm yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Because they needed to dry basically in 93 minutes, so the only paint that could dry fast enough was a paint called Japanese Black. So the reason was speed.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Not customization. In 1926, they started making different colors again because Duco Lacquer was invented, and Duco Lacquer allowed them to paint in colors and have it dry as fast as Japan Black dried.

Dave Young:

The vision to say, okay, well that’s our bottleneck, we’re going to eliminate the bottleneck by reducing choice. And I suppose in those days you could go get your car painted by somebody else.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. But they were forced to reduce it to one color.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Simply because that was the only one that dried fast enough until they could figure out how to make other paints dry fast.

Dave Young:

Well, and you probably know the answer to this, but it wasn’t let’s put out a car every 93 minutes because we’re stockpiling these cars. We think that eventually people are going to want them. No, there was demand.

Stephen Semple:

Absolutely. They were trying to meet demand because they dropped the price to the point where the everyday man could buy a car. One-half of the cars on the road were Model T Fords.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Which is just absolutely remarkable, and the impact it had on the world is just staggering. But here’s the thing. We often hear businesses go, “you know, my idea that I’m going to do is I’m going to reduce prices, and that’s going to create this big demand.” And we’ve seen businesses do that, but it’s not by reducing prices a little bit. Cars were two and $3,000.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

And he brought them down to $425, right? One-fifth of the price. That’s not a small drop. That is a staggering drop. The other thing that he changed in terms of business models, Henry Ford is the common thing in businesses at that time was to distribute profits, all the profits to the shareholders. He created this idea of “No, we’re reinvesting to build further plant and equipment and automation to stay ahead of the competition” because they stayed ahead of the competition for a long time.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

For many, many years, but it’s not about expanding your market and really making a difference using price as your strategy. You can only use price as your strategy — it’s about dropping the price by a staggering amount –and typically, for that to occur, it means you have to change the cost structure of the business.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

You’ve had to come up with something that so dramatically, that’s also hard to copy, but that dramatically changes the cost structure that you’re able to just go, I’m going to drop it down, and we’re going to have other examples in other podcasts of businesses that have done that.

Dave Young:

All right. That’s a terrific one, though. Henry Ford. A great giant to stand on the shoulders of, I guess.

Stephen Semple:

Great giant to stand on the shoulders of. Take a look at those pictures. It is mind-boggling when you think about the change and when you think about even things like how quickly then gas stations would have had to develop and mechanics and roads. I mean, it’s just-

Dave Young:

Yeah. Everything you need to put millions of cars on the road. Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Absolutely. The speed of change at that time was just remarkable.

Dave Young:

Thanks for listening to the podcast. Please share us. Subscribe on your favorite podcast app and leave us a big fat juicy five star rating and review at Apple podcast and if you’d like to schedule your own 90 minute empire-building session, you can do it at empirebuildingprogram.com.

- Branding Beyond the Gold Rush: The Levi’s Story - December 29, 2025

- Tapping Into the Zeitgeist: Monopoly’s Origin Story - December 17, 2025

- From Mars Men Mediocrity to Sour Patch Success - December 10, 2025