Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Blubrry | RSS | More

At the top of their game the Wrigley’s family was one of the wealthiest families in the world. From Wrigley Field in Chicago to Wrigley Mansion in California. Learn how they broke into the big time when they actually had nothing to sell.

David Young:

Stephen, my notes say we’re going to talk about Wrigley.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. And the interesting thing, we’re going to talk about Wrigley, not as a multi-billion dollar empire, but what Wrigley did back when they were a little Midwestern, $170,000 a year business. They were founded in 1891 by William Wrigley Jr., and in 2016, they basically merged with Mars.

And at that time, they had six billion in revenues and about 1,600 employees. But when we go back, they were a little Midwestern, gum company that wanted to go national. And in fact, one of the things that they did early in their history is they did this little $100,000 advertising campaign. They were in Chicago and they wanted to move into the big market of New York. And they did this $100,000 advertising campaign that totally failed.

David Young:

This is when?

Stephen Semple:

This would have been back in the late 1800s, early 1900s.

David Young:

$100,000 was a lot of money.

Stephen Semple:

It was a lot of money, but the campaign failed. And part of the reason why they felt it failed was they didn’t feel like they could get enough attention with that campaign. But here’s where things get really interesting. In 1907, there was kind of this little mini market crash and panic happened. And everyone stopped advertising and the ad rates dropped. Does this kind of sound familiar at all?

David Young:

Mmhmm.

Stephen Semple:

We see this happened in the pandemic. We see this happen in recessions. We see this happen over and over again. But what Wrigley decided to do, this is how bold this guy is, he went out and he borrowed a pile of money. So he borrowed $250,000 to run an advertising campaign.

So right when panic is hitting the streets, no one’s advertising, he said, “I’m going to spend $250,000 on this campaign.” And he feels that the value that they got was what would be comparable to a million and a half dollars worth of advertising.

David Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

Over 250 grand, they got a million and a half dollars worth of advertising. Here’s what happened. It worked gangbusters. They went from $170,000 a year business to a $3 million business in three years. So from 1907 to 1910, they went from 170 grand to three million in sales. That’s like 1600% growth, 16 times growth in three years.

David Young:

All he had to do was beat the percentage rate he was paying on the loan.

Stephen Semple:

There you go. Yeah, exactly. From that day on, they stayed a national advertiser. And Wrigley was often quoted as saying, “The key in advertising is, ‘Tell them quick, tell them often.’” So he was big believer in repetition.

David Young:

Tell them quick and tell them often. It sounds a lot like the kinds of things that we tell clients.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah.

David Young:

Today.

Stephen Semple:

Yes. Tell them quick, tell them often. But here’s the interesting thing. They didn’t just do this trick once. So by 1932, they were doing $12 million a year in profit. 1932.

David Young:

In profit? That’s not gross.

Stephen Semple:

In profit. And they were the largest advertiser in the United States. But the story doesn’t end there. The son took over the business, Philip Wrigley, and they stayed advertising. And then World War II came along. So they’re already a pretty big business going to World War II.

David Young:

And the war changed everything for everybody.

Stephen Semple:

They no longer made gum. They were now making food and things like that for the soldiers. So if you couldn’t sell your product-

David Young:

So they couldn’t make gum?

Stephen Semple:

Couldn’t make gum, couldn’t sell gum. What would most people do? And they go like, “I can’t sell the product.” You’d stop advertising.

David Young:

Yeah. Or you’d figure out, “How are we going to advertise canned beans?” Or whatever we’re making now.

Stephen Semple:

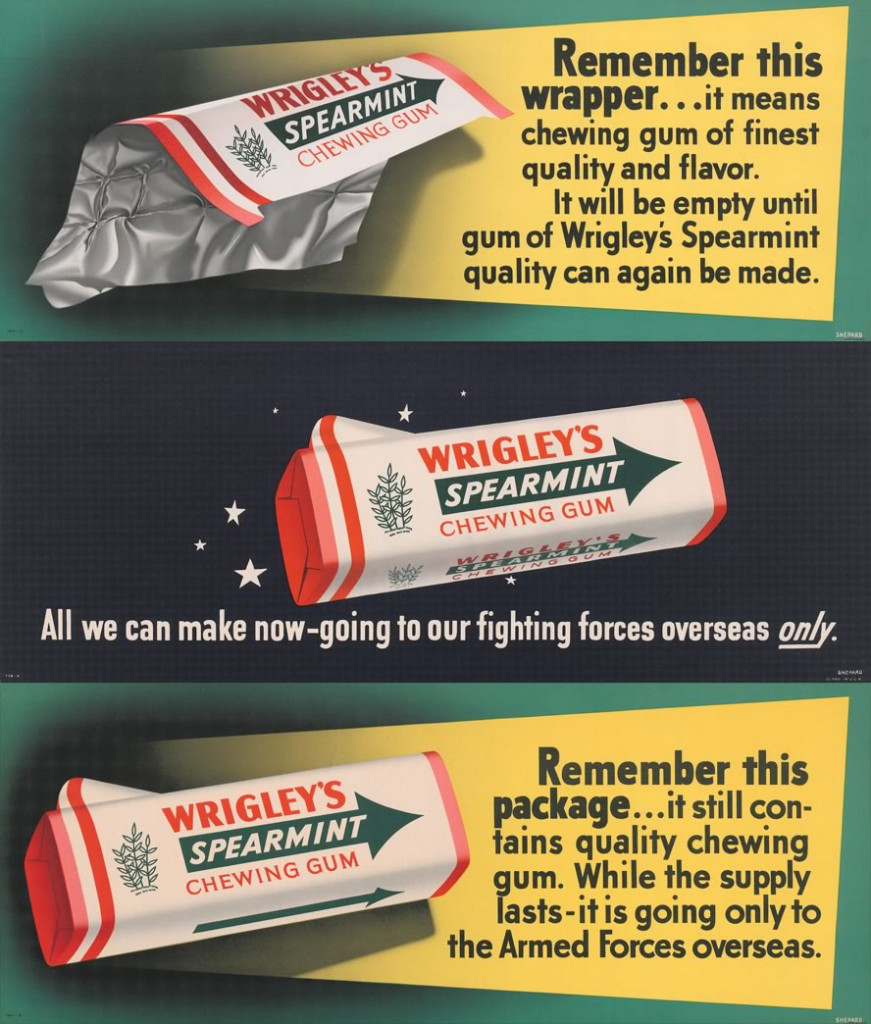

Right. Yeah. So no, they continued to run advertisements through the war. Because their belief is, the war will end and when the war ends we want to be selling gum again. They had ads running, showing empty packets of gum with the ad saying, “Remember the wrapper”. They ran ads hearkening back to pre-war times. When you’d like to go back to that time, remember the wrapper.

Stephen Semple:

When sales started in 1946, they passed the pre-war numbers immediately. Went past what it was before the war a significant amount. So the thing that I found interesting about Wrigley is not only did they do the trick once, of we’re going to advertise when others aren’t advertising… The dad did it and then the son did it in World War II. And then they went on to become this $6 billion empire.

David Young:

So in times like this, is this the lesson? You need to think about the fact that these weird times are temporary.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, I think there’s two lessons. One is to look for the opportunity in the weird times. And the weird times are temporary. But the weird times don’t come along every year. The weird times come every so often, although we’re in a historic weird time right now that could repeat itself again in six or nine months.

But there’s also a lesson for every year. And Dave, you see this with your customers in the heating and air conditioning business. How many people in that industry, when they go into the shoulder season, say, “I’m not going to advertise”?

David Young:

Yeah. Pull in and let’s wait for summer.

Stephen Semple:

Right. We’re going to advertise in the summer. So Wrigley was looking at that. He’d go, “Well, if people aren’t advertising, if my competition is not advertising in January and February, my competition is not advertising during the war, I’m going to advertise.” My competition is not advertising in January, February, and March or September, October, I’m going to advertise.

David Young:

Talk about being able to buy share a voice. It’s one of the ways that you can take your ad budget and stretch it. Especially if your competitors are not around, you can buy an increased share of voice with maybe the same money that you had been spending all along, as long as you just don’t stop.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah.

David Young:

And there’s been very recent research that shows that share of market lags share of voice. So as you build your share of voice during times when your competitors aren’t on, or you outspend them in share of voice, your share of market will catch up to that.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. And for our listeners, share of voice is this idea of, how much are you heard versus your competitors? So it’s this whole idea that if I have a really loud competitor, it’s hard for me to be heard. But if everything’s quiet, a whisper is even heard. That’s the idea of share of voice. And share of market is, what’s the percentage of the market that you’re achieving? So you’re absolutely right. Share of voice leads share of market.

And Wrigley really proves this because they had two big opportunities where everything went really quiet and they went unbelievably loud. Think about it. And in the New York one, his first advertising campaign was a 100 grand. And then when everybody went quiet, he doubled down on it. He said, “You know what? This time I’m going to spend $250,000.” So he was massively loud in that market. And sales just exploded for them.

World War II. Lots of people weren’t advertising in World War II because there was lots of things not being sold in World War II. He couldn’t sell his product in World War II, but he said I’m going to keep talking to people. I’m going to create that demand. I’m going to own that share of voice really for small dollar amounts. Our customers can do the same things when times are tough. I get it, it’s hard to write those checks. But small checks — when everyone’s quiet — buys you a lot of influence in the marketplace.

David Young:

Absolutely. Great lesson. And I think it’s important that we remember these stories. We tend to think of those businesses like Wrigley’s as just this giant entity, because that’s what they are today, or that’s what they became by the 2000s. They were everywhere, but then it just wasn’t always so. Everybody starts out tiny. Nobody builds a giant business from the get-go.

Stephen Semple:

Right. But they become giant by doing something bold. Doing something a little bit crazy and out there. And if you want to build an empire, you got to be a little bit bold.

David Young:

Be a little bit bold. Thanks for listening to the podcast. Please share us. Subscribe on your favorite podcast app and leave us a big fat juicy five-star rating and review at Apple Podcasts. And if you’d like to schedule your own 90-minute empire-building session, you can do it at empirebuildingprogram.com.

- How’d The Bananas Build a Million-Person Waitlist? - July 2, 2025

- Innovation or Iteration? Spin Master’s Paw Patrol Playbook - June 23, 2025

- Lip Bar – Think big, start small. It’s better to fail than regret. - June 16, 2025