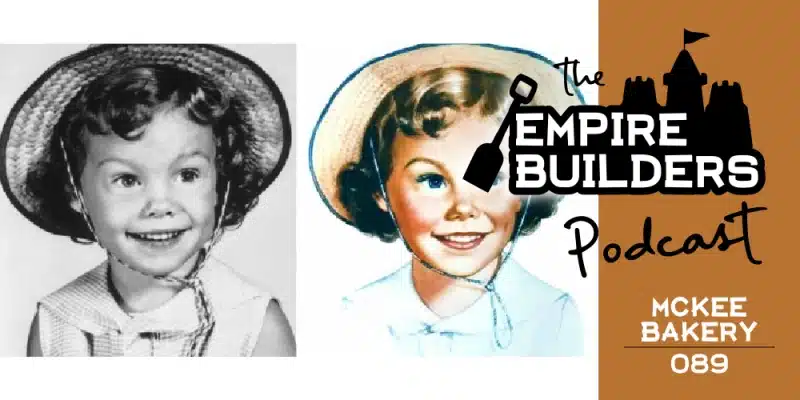

Third generation run company including the granddaughter who inspired their famous brand, Little Debbie. She now sits on the board of directors.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Blubrry | RSS | More

Dave Young:

Welcome back to The Empire Builders Podcast, and Stephen I’m excited because we’re back to baked goods. You told me just before we started recording that we’re going to be talking about McKee Bakeries, and I didn’t have a clue. I didn’t have the foggiest notion what that was till you said, “Oh, these are the people behind Little Debbie snack cakes.” So, yeah, yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Have you partaken in the few Little Debbie’s in your time?

Dave Young:

Yeah, I’ve probably eaten loads of them in the past. I’m trying to avoid that stuff at this point in my life. Well, one of the weird experiences I have with Little Debbie’s is, this is a weird one because I was renting a storage unit in Tucson, Arizona a couple years ago. You know how sometimes they’re really cramped in the spaces to get in and out of your storage unit. Every time we’d try to go to access our storage unit, the guys right across from us had their trucks in, their trailers pulled in there and they were loading in and out boxes and boxes and pallets of Little Debbie snack cakes. It’s like these were obviously the franchise drivers, the route drivers or whoever, and they were keeping their … I don’t know how that any of that works. So maybe that’s part, I don’t know what their business model is, but it evolved storage units in Tucson, Arizona somehow.

Stephen Semple:

Wow. There you go. Maybe these were counterfeit Little Debbie’s.

Dave Young:

It could’ve just been a front, right? The cartel uses empty Little Debbie cases. I have no idea how any of this works. So tell me about McKee Bakeries.

Stephen Semple:

Started as McKee Bakery and it’s now known as McKee Foods. And as we talked about, it’s best known for the Little Debbie brand. Here’s one of the things that’s kind of cool. The company is still privately held going into its third generation, so we don’t exactly know the sales figures. What I did come across as about 900 million cartons of Little Debbie product is sold a year, so that’s a lot of storage containers in Tucson.

Dave Young:

That is a lot of storage units. I don’t know if there’s even a way to calculate that.

Stephen Semple:

And the fun part is the Little Debbie brand, like the whole picture and idea is actually based upon one of the founder’s grandchildren with four year old Debbie, who today serves as an executive VP on the board. So Little Debbie has grown up and is now on the board of McKee Food. And so I thought that that was pretty cool. And so still very much a family business.

Dave Young:

That is really cool that they’ve managed to grow to that size and keep it in the family. That’s always amazing.

Stephen Semple:

Don’t see that very often. So they’re doing something right, not only in terms of the business, but they’re doing something right in terms of the family that they’ve been able to keep this going and keep it being successful. And I thought that that was very cool and just kind of neat that Little Debbie’s on the board.

Dave Young:

So how did this thing get started?

Stephen Semple:

It started during the Depression when O.D., he’s called O.D but his name was Oather but he goes by O.D, and Ruth McKee started this little bakery business during the depression. And what O.D. started doing was selling 5 cent Virginia Dare cookies out of his 1928 Whippet car. And then he wanted to expand. Things were doing fairly well. He wanted to expand so he bought the small bakery, which was called Jack’s Cookie Company.

And at this time, Ruth joined the business full-time to run the office and they had a housekeeper taking care of the kids. And if you think about this, we’re talking in the 1930s she’s running the office and someone’s taking care of the kids. That’s visionary in so many ways, so many ways, which also was one of these things that really stood out to me about the McKees. And it did well for a number of years. And they owned this business with their father-in-law and they wanted to expand it further but the father-in-law didn’t want to expand. So Ruth and O.D. basically sold their shares. They moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, where they started a new bakery. They wanted to start a new business in Charlotte, North Carolina. And it didn’t do so well.

And then in 1950s, Ruth’s brother, Cecil King, was in poor health. So they moved back to Chattanooga to help out with the family business. So here they are, failed baking entrepreneurs. They got lots of debt. They’re looking for a fresh start. They’re helping out Cecil, who just can’t keep up. And the business is doing private label baking at this point. And Ruth looks at the books and she realizes, you know what? They’re losing money on every cake they make. This private label business while it’s big volume is really not working out for them. And at the same time, Cecil decides with his health and whatnot that he’s selling the business.

So O.D. and Ruth decide to buy. Now they have no money, but it’s family and the family’s willing to sell it to them on an installment plan. So now they have this business and even more debt and they need to find a quick way to make money. So the first thing that they do is look at this idea of lowering production costs. And O.D. comes up with this idea of creating single serve cakes, little snack cakes. This idea is not popular yet. And while it doesn’t actually reduce manufacturing costs, it reduces the sticker price. And that small cost lets you increase the margin, right? Because the cake’s one eighth of the size, but it’s not one eighth of the price.

Dave Young:

Right. Right.

Stephen Semple:

Now at this point, Ruth looks at the idea but she doesn’t like the idea. O.D. decides go in a different direction and he creates a new treat. He’s known for his oatmeal cookies. Because remember, they had a cookie shop at one point. What he wanted do was figure out a way to keep these oatmeal cookies soft. And what he discovered was if you put cream between them, it keeps them soft. And so he created the oatmeal cream pie.

Dave Young:

Nice.

Stephen Semple:

But there was also this challenge, how do you keep them fresh and keep them from breaking? And this was the future for them when he figured out this challenge. And what he realized was you can wrap the treats and plastic. And this is a revolutionary idea. Plastic is not being used a lot at this point in the food business. Up to this time, baked goods were bagged. But if sealed them in this plastic with this cream, he found it seals in the freshness, keeps the cookie soft. They also started using vegetable shortening, which added shelf life.

So in 1952, they launched the oatmeal cream pie and it’s a huge hit. Great margin. You pay more per ounce for the small size. People paid for the convenience. And in fact, they’re unable to keep up with the demand. Demand is amazing. But they’re still in debt, they’re struggling to keep up. They don’t have money to expand. And here’s where Ruth’s brilliance really … Like man, she was able to think outside of the box. So she proposed a really unusual partnership. So they’re both graduates of Southern College, so she approaches the college to build a factory. The students will get a job and the experience and they’ll bake the goods.

Dave Young:

Oh wow. Okay.

Stephen Semple:

And the college goes for it. They go, this is a great idea. And that doubles the production overnight. Like talk about thinking outside of the box. Ruth is just awesome in terms of thinking about this and selling the ideas of the college. You guys build the factory, we’ll make our stuff there and it creates jobs for the students.

Dave Young:

Yeah. Well see, the traditional sweatshops had not been invented yet.

Stephen Semple:

So they went this way instead.

Dave Young:

So go with the college students.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah, there you go. Now they’re still doing private label at this point, and they decide that they want to build their own brand. They want to own and control their future. Doing this private label, even creating this new product idea and private labeling it, they just weren’t in control, margins are thin, all of that sort of stuff. So they decide, you know what? We want to go down this building a brand. So in 1960, they decide the change of their business model, build their brand, and they hire an expert to help them package. They hire a guy by the name of Bob Moser. And the first thing the Bob says, “You should come up with a name.” And he suggested a kid’s name. Why don’t we do a kid’s name for this? And so they pick their four year old granddaughter, Debbie. So it becomes Little Debbie. And they even add a picture to the box, which is actually based upon a photo of Debbie. The illustration we see is based upon a real photograph of Little Debbie.

Dave Young:

Nice.

Stephen Semple:

So in 1960, they launched Little Debbie’s and it’s boxed in a box of a dozen with each individually wrapped. And this becomes like a lunchbox item. And they really-

Dave Young:

Oh, yeah, yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. And it was the first sort of lunchbox item that come along and they corner the market on this whole idea of individually wrapped snack cakes. Now around this time, a lot of other entrants start coming into the market and the shelves start getting crowded. And so they realize again, they need to stand out and what’s new at this point is tv.

So they decide to pour money into a marketing blitz and really lean into television. They’re, again, one of the first to do this whole idea of this large media buy on television to sell this small priced item. And if anybody’s interested, we have a podcast we did in the past around this whole idea of why does a chocolate company do national campaigns for these small priced goods? And we walk through the math on that. So a person can certainly go back and revisit that episode. So they lean in the television, it works amazing. During this time from basically 1960 to 1970, they expand manufacturing 13 times. They’re just killing it. Then in 1973, they create another new idea. O.D. looks at it and says, “What if we created four new snack cakes and put them all in one box and created this variety pack?” Because he looked at how this was a lunchbox item. It was a lunchbox item, but it’s kind of boring having the same thing in the lunchbox.

Dave Young:

12 different days. That’s two and a half weeks of lunch.

Stephen Semple:

Right. So why don’t we create these four cakes, create this variety pack. And that’s what they did. And today they’ve grown huge, they’ve got a whole bunch of products, but their main one is still the Little Debbie’s. And they do, it’s estimated 900 million cartons a year of Little Debbies and four of the founders grandchildren representing the third generation of the family are managing the business, including Little Debbie herself, which is very cool.

Dave Young:

That’s pretty amazing. Do you know anything about their business model itself? These guys that were renting these storage units, is it a franchise? Is it like the Frito-Lay drivers? You buy a route from them and now you’re the guy. It feels like that’s the same thing.

Stephen Semple:

It wouldn’t surprise me. I don’t know. I didn’t go down that path. I was just sort of, to me, the thing that was really interesting was this innovation that Ruth and O.D. did around the creating of the cakes and the packaging. And that’s what I really explored. And I also thought third generation business and it’s still successful, that’s very, very rare. It is amazing how many really massive companies don’t make it through generation three. So they’re doing something right not only in the business, but also how they’re teaching their kids because it’s a really, really special, very special thing. The other thing that I thought was quite interesting was how O.D. approached the whole problem of bringing down manufacturing costs. Instead of bringing down manufacturing costs, maybe the thing to do is change sizing.

Dave Young:

Oh gosh, it’s so smart. Right?

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. And which also then changed the dynamic of what is somebody paying for? Well, what I’m actually now paying for is convenience. And now that I’m paying for that convenience, I am willing to pay that little bit more. So I thought it was a really interesting way of looking at the problem and putting the problem on its head and saying, “Well look, there’s a different way to approach this challenge.” And I thought that that was really, really brilliant. Between that bold enough and creative enough to approach universities and sort of go, let’s build this facility, they showed themselves to be very, very innovative thinkers.

Dave Young:

You think about the idea of they’re already wholesaling, right? They’re doing private label and you can decide to not be a wholesaler anymore or you can decide, hey, we’re going to sell the same product to the wholesaler, but we’re going to chop it into a whole bunch of little pieces, wrap it up, and they’re going to pay way more than they did for the whole sheet. And we’re still wholesaling.

Stephen Semple:

Yes.

Dave Young:

Right? I mean, that’s just so smart.

Stephen Semple:

Yeah. Because that was the first step. The first step, they didn’t dispose of the wholesaling model. And then the next thing that they did that I thought was again, very, very smart … And look, it’s a hard transition to do, is this idea of if we’re going to really and truly control our future, control our pricing, make the extra money, we need to have a brand. Or how I like to put it, we need to have the relationship with the consumer. The consumer has to want our product. We need them demanding us, and then we need to advertise that so that people then know about it, want it, and desire it. Because suddenly when you’re in that position, you have the power. You have the power, you have the margin, you have control of your destiny and future when you’ve got that direct relationship with the customer through your brand.

Dave Young:

Absolutely. And it’s still wholesaling. I mean, they still need grocery stores and snack shops to stock this item, or at least to buy it from these guys that have the storage units in Tucson. Again, I don’t know how that works. But at the same point, you’re still wholesaling and you’re controlling the brand. And we’ve visited this on several episodes where you’re advertising your brand and you’re getting people to walk into the stores and ask for it by name, right?

Stephen Semple:

Yes.

Dave Young:

That’s the big power of building a brand around a product that you’re really wholesaling and you feel like you don’t have a lot of control, but you do if you create a brand that people want and ask for.

Stephen Semple:

So to me, this really spoke about the power of brand, power of convenience, and this real innovative thinking that O.D. and Ruth brought to the business, I thought was really very, very cool. And it’s also fun that, again, Little Debbie’s on the board.

Dave Young:

Yeah, there’s her picture, but she’s sitting in a big, nice, comfy chair in the boardroom. Not bad, not bad.

Stephen Semple:

Not bad, not bad. She’s done well.

Dave Young:

Well done, Debbie.

Stephen Semple:

That’s right. Awesome.

Dave Young:

Thanks for that story, Stephen.

Stephen Semple:

Thanks, David.

Dave Young:

Thanks for listening to the podcast. Please share us. Subscribe on your favorite podcast app and leave us a big fat juicy five star rating and review. And if you have any questions about this or any other podcast episode, email to questions@theempirebuilderspodcast.com.

- How Alienware Spotted Unidentified Flying Opportunities - February 4, 2026

- Hexclad – A failed actor’s rise from broke to $1 billion - January 27, 2026

- Dr. Gross Skincare – Better to be gross than boring - January 20, 2026