People buy transformation. From unhappiness to happiness.

But what if they don’t know that they’re unhappy?

Or maybe the customer vaguely senses it, but doesn’t have a name for it, let alone awareness that there’s a solution for it.

Or maybe the customer vaguely senses it, but doesn’t have a name for it, let alone awareness that there’s a solution for it.

Or maybe they know there’s a solution, but it’s a satisfactory solution.

This is when a smart advertiser will “name the disease.”

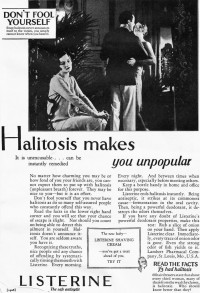

Nobody knew bad breath was a destructive social ill until Gerard Lambert pointed the blinding spotlight of his ads at the dangers of halitosis as a means of selling Listerine.

The ads not only named the disease, they taught you how to recognize its symptoms, too.

Brilliant way to use constructive discontent as a selling tool.

Shame is always much more powerful than vapid promises of sweet-smelling breath.

Whisk Names the Laundry Disease Caused by “Powders”

For a slightly more modern example, there’s Whisk’s classic ad campaign featuring “ring around the collar”

Whisk was the nations first liquid laundry detergent. So it could be used to easily pre-soak stains.

And the most common stains were sweat stains around collars.

Calling those stains “ring around the collar’ was a powerful way to name the disease — not to mention to straight-up shame housewives into buying the product!

These ads made Whisk a #1 seller of laundry detergent in their day.

James Jordon Strikes Again with “Zestfully Clean”

Then there’s “Zest” which was one of the first soap bars to add detergents to prevent the formation of “soap scum” on the customer’s skin.

Zest was an also ran in its category until the brilliant James Jordon (who also created Whisk’s “ring around the collar” campaign) came up with “zestfully clean.”

Because if only Zest gets you Zestfully Clean, then what does soap get you?

Filmy!

This is a great way to imply the “disease” by contrast.

Yes, there’s a solution for being dirty and needing to wash up, but it’s not a perfect solution.

By calling out the shortcomings of soap, the brilliant “Zestfully Clean” campaign made Zest a top seller.

Dominos and What to Call Delivery Pizza that’s Cold or Damaged

Then there’s one of my favorites in this class of “Name the Disease” commercials: Avoid the Noid.

Back in the 80s and 90s, Delivery Pizza was a thing. But it wasn’t exactly perfect.

Sometimes the pizzas came late. Or cold. Or somewhat banged up.

Delivery pizza was a solution, but one that left some things to be desired.

Domino’s fixed all that with fast delivery of piping hot, fresh pizza.

But to highlight the problems with other delivery pizzas, they created the “noid,” which led to ads like this:

The Psychology Behind Naming the Disease

Russian psycholinguist Lev Vygotsky proved the power of naming with the following experiment:

He asked a group of very young students to draw butterfly wings, and noted the following:

- Those children who already had words in their vocabulary for dot, triangle, slash, and other shapes were able to draw the butterfly wings well, even from memory.

- Those children who did NOT have words for shapes in their vocabulary were unable to draw the wings even when looking at them, in any way that they could later recognize what they had drawn.

- When half of the children from the second group were taught the names of the important shapes, all of those children could then satisfactorily draw the butterfly wings, even from memory, while the other half, who remained unable to name the shapes, showed little improvement.

In other words, if you want customers to be able to recognize and become fully conscious of their dissatisfactions, you have to name them.

In other words, if you want customers to be able to recognize and become fully conscious of their dissatisfactions, you have to name them.

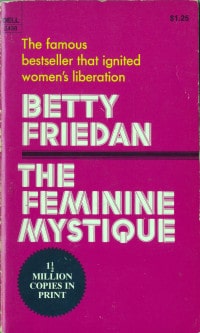

It’s a lesson Betty Friedan understood when she gave the vague dissatisfactions of 50s era housewives the peculiar name of “The Problem that Has No Name”

And it worked like magic to push her agenda. Advertising magic, baby!

Apply This to Your Advertising

So maybe your industry has customers that already KNOW they’re unhappy.

And you’re thinking: “I don’t need to name the disease”

Then again, maybe they know there’s a solution, but they’re not quite happy with the solutions they know about.

Making it your turn to name that problem for them, so they can demand a better solution.

The solution that you’re providing, naturally.

See how it works?

Name that disease, brother!

- Getting a Foot in the Door — Of Perception - November 27, 2025

- What Digital Superstars Know About Offline Advertising - November 17, 2025

- Unmistakable: A Tale of Two Boots and Branding Done Right - November 8, 2025