What are you trying to make happen?

Start with that question.

And ask that question of the business first, not your advertising.

Now here’s the real challenge:

Don’t let yourself get away with a general response. Force a specific answer.

For example, in the mid-1980s, Pizza Hut could have answered the question with:

“Sell more pizza and make more money”

A theoretically correct answer, but overly general.

Mid-80s Pizza Hut was already quite busy with dine-in customers for dinner, especially during the weekends.

Their problem was their lunch trade was lackluster.

So the REAL answer to “What are you trying to make happen” isn’t just “sell more pizzas and make more money.”

The real answer is: increase the number of lunch-time customers so we can sell more pizzas during the week.

Now this is where things get tricky — and where the next question comes in.

Why Aren’t They Doing That Already?

I say this is tricky because there’s a HUGE difference between trying to get more of a market that actually exists and chasing a market that only exists in the fantasies of the business owner.

Every business owner wants a perfectly smooth demand curve.

One with no seasonalities or slow periods.

And that’s a pipe dream.

So when a restaurant wishes to be “just as busy” during weekday lunch hour as Friday night dinner, that’s a wish-fulfillment fantasy.

Any honest ad consultant should push back on that delusion.

But if a restaurant wishes to merely increase lunch hour business, that might well be doable, especially if that lunch hour customer already exists and is currently won over by competitors.

That’s when an honest ad consultant will ask the second key question:

Why aren’t customers already coming in for lunch? Why are they going someplace else instead?

With mid-80s Pizza Hut, people were avoiding the restaurant because they thought of it as a sit-down-and-enjoy yourself place.

Meaning that a trip there would take awhile. As in too long for lunch.

Plus, one normally splits a pizza with someone, which is fine for dinner, but maybe a touch awkward with work colleagues.

And this is where the final questions come in.

Are Customers Right About That? And What Can We Do to Change Things?

Sometimes customers’ objections are based on misperceptions.

Then advertising can aim its persuasive messaging at those misperceptions to drive more business.

A great example of this is Rolling Stone’s legendary Perception vs. Reality ad campaign, also from the 1980s.

Rolling Stone had a massive audience and an engaged readership, which meant they should have been making a mint on advertising.

Except they weren’t, because ad buyers tended to dismiss Rolling Stone readers as dope-smoking hippies who weren’t a valuable target for ads

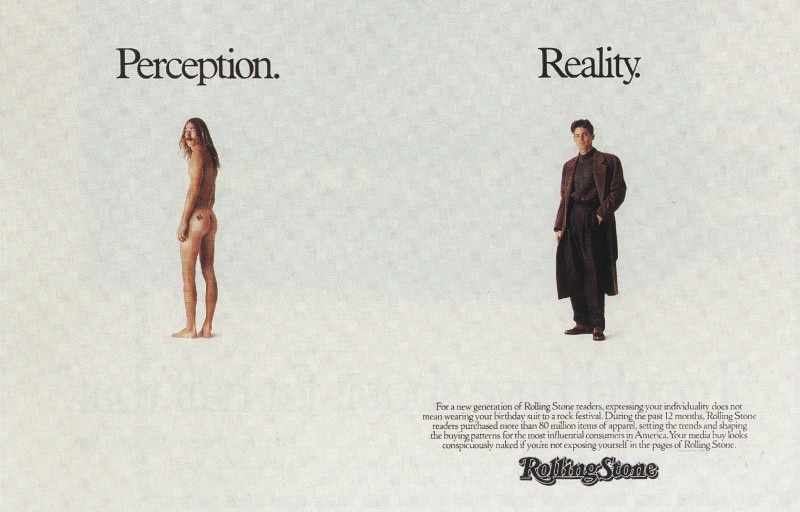

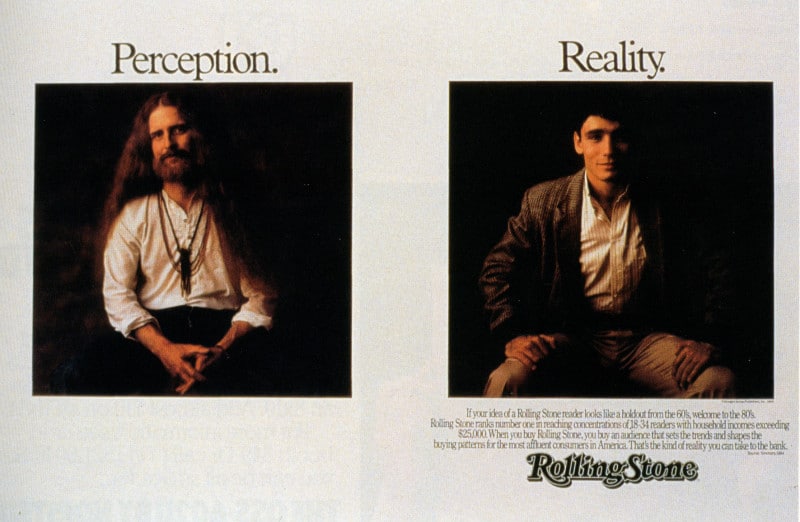

So in 1985, Rolling Stone hired Fallon McElligott to create ads like the following:

The copy reads:

“If you still think Rolling Stone reader’s idea of standard equipment is flowers on the door panels and incense in the ashtrays, consider this: Rolling Stone households own 5,199,000 automobiles. If you’ve got cars to sell, welcome to the fast lane.”

The copy on this one reads:

“For a new generation of Rolling Stone readers, expressing your individuality does not mean wearing your birthday suit to a rock festival. During the past 12 months, Rolling Stone readers purchased more than 80 million items of apparel, setting the trends and shaping the buying patterns for the most influential consumers in America. Your media buy looks conspicuously naked if you’re not exposing yourself in the pages of Rolling Stone.”

Here the copy reads:

“If your idea of a Rolling Stone reader looks like a holdout from the 60’s, welcome to the 80’s. Rolling Stone ranks number one in reaching concentrations of 18-34 readers with household incomes exceeding $25,000. When you buy Rolling Stone, you buy an audience that sets the trends and shapes the buying patterns for the most affluent consumers in America. That’s the kind of reality you can take to the bank.”

That ad campaign worked like a charm; Rolling Stone’s ad revenue increased 47% in the first year alone.

And the campaign ran long enough for it to feature 50 of these ads.

That makes this campaign a textbook example of what to do when it’s buyers’ perceptions that prevent the sale AND those perceptions don’t match reality.

But what if those buyer perceptions are accurate?

Address The Reality, Then Target the Perception.

For Pizza Hut, the buyer kind of had a point to their lunch-time objections.

It WAS a sit-down pizza place, and baking that pizza DID take time.

Plus, it might be awkward to split a pizza with a co-worker, or to eat there alone and be forced to doggy bag half a pie.

So Pizza Hut came up with the Personal Pan Pizza — a pie sized for a single eater and capable of cooking much more quickly than a full-sized pizza.

Then they launched the following campaign:

And note that they put a hard number to the most pressing concern of the buyer — your personal pan pizza will be out in just 5 minutes or your next one is free.

Bam! Problem solved, lunch-time business boomed. And Pizza Hut did, in fact, sell more pizzas and make more money.

But that kind of success only happens when you align your persuasive strategy to your business needs BEFORE you decide on the right ad creative.

What About Your Advertising?

Have you bothered to ask yourself:

What are you trying to make happen?

Are you forcing a specific and granular answer?

Have you also asked yourself:

Why aren’t customers doing what you want them to do already?

And if it comes down to customer perception, have you bothered to ask:

Are they right about that? And what can you do to change things?

Because if you don’t ask the right questions, you’ll end up with the wrong answers (read, “advertising”).

Of course, sometimes it helps to get a consultant in to guide you through this process. And for that, I’m always happy to help.

- Are You Paying for Too Much for the Wrong Keywords? - July 15, 2024

- Dominate Your Market Like Rolex — 4 Powerful Branding Lessons - July 3, 2024

- Military-Grade Persuasion for Your Branding - June 25, 2024