In all forms of storytelling, which is an essential building block of good branding, it is always better to show someone why something is true rather than simply telling them a true statement.

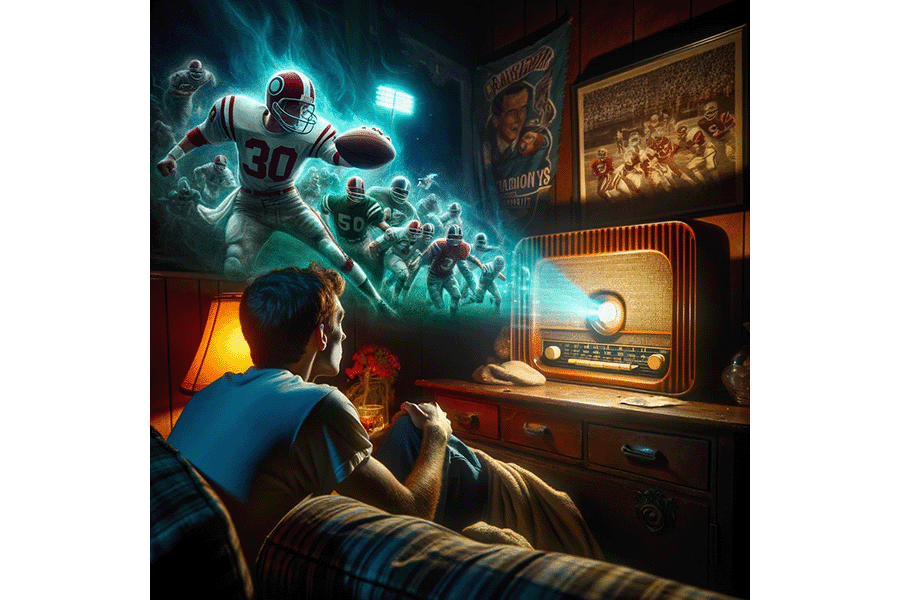

Think of the world of sports and any time you hear a heart-warming tale about a high school football benchwarmer who spent an entire summer lifting weights and getting into incredible shape, stayed late after every practice, and memorized the playbook forward and back, with all that hard work culminating in a game-winning play at the end of the season.

Hearing those details and building a picture in your mind anchors the fact that our football hero left nothing to chance and showed world-beating dedication to succeed at something he loved. You feel like you know him, want to pat him on the back, and have him take your daughter to the homecoming dance because he’s a young man of fortitude and grit.

Now imagine if, instead of reading vivid accounts of our player, you simply read that “He worked extra hard in the off-season and improved from the previous year.” Same information, but zero resonance, and you’ve already forgotten what you just read. That’s the critical difference when it comes to “show, don’t tell.”

Branding, like selling, is all based on emotional investment and the connection that gets built with expert storytelling that an audience is exposed to in a calculated and systematic way. Numbers and facts can play an essential role in that mix, especially when it comes time to make a decision, but at best, hard data gets used to justify an action that is taken because of emotional instincts.

At the top of the list of any great storytelling strategy is the practice of framing a story, deciding from the beginning what pieces will be revealed and what will be excluded to build curiosity and investment in the audience.

Advertising, like every other kind of storytelling, should always begin with a framing sequence. In the prologue of John Steinbeck’s Sweet Thursday, a character explains the attraction of the partial reveal: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks.”

Here’s the start of a recent ad Roy Williams wrote:

“Mr. Jenkins?”

“Yes, Bobby.”

“How much should a hamster weigh?”

We know from this framing sequence that Bobby respects the wisdom of Mr. Jenkins and feels comfortable enough around him to ask whatever is on his mind. And because Bobby feels comfortable, we feel comfortable, too. We find out later that Mr. Jenkins owns an air conditioning company.

A different campaign’s ad begins as the owner, Ken, says:

“Zach, have you ever heard of the 7-year itch?”

This 10-word frame skyrockets our curiosity. We want to hear the answer and learn where Ken is headed with this question.

“Five years before Teddy Roosevelt led the Rough Riders, Simon Schiffman stepped off the train to stretch his legs.”

Two heroic icons of American history 125 years ago… An unknown man steps off a train… Framing has set the stage. Now captivate your customer’s attention by surprising them with what happens next.

- Leading the Bull - September 24, 2024

- Pioneers and Settlers - September 16, 2024

- Bigger Than Me - September 9, 2024