Magician, Comedian, and Modern Rogue, Brian Brushwood has a fantastic concept for creating and growing an audience from scratch.

And as the star of several successful broadcast and internet TV shows, Brian’s a certified expert at growing audiences.

Brian’s concept is the Story —> Attention —> Sale cycle:

“Let’s say you are a screenwriter convinced you have a billion-dollar screenplay.

What you have is a billion-dollar story.

What you want is to see it made into a movie.

The temptation is to go the wrong way in the circle, which is to go to Hollywood… [and try to make the sale, only to have the studio]… make a movie over which you have no control, no say, and no authority…

If it’s truly a billion-dollar story, then it will also be a billion-dollar story as a book.

If it’s a billion-dollar story as a book or a series of books, it’s also going to be a billion-dollar story as a weekly set of Tumblr blog posts, chapter by chapter, or as a podcast. It will continue to be a billion-dollar story all the way down to that atomic unit of storytelling, a Tweet, then a series of Tweets.

If you’ve got a story, use it. That’s how you get attention.

Story – Attention – Sales.

… People tend to want to go backwards on the circle (if you have attention, you race backwards chasing story. If you have money, you race backwards to purchase attention. If you have story, you race backwards to sales/money.)

….So to me, the only virtuous circle is: start with a great story. use it to build great real estate in the minds and hearts of others (attention), and carefully harvest that (sales), so you can invest in even better stories. This is the way producers and big-money influencers think.”

Did you get that?

You can’t efficiently gain attention without a great story

A story that you basically give away, for free.

If you try to buy attention without a story, you’ll strike out.

This is what happens to most advertising and marketing efforts.

People buy “exposure” via advertising.

And presume that they’ve also purchased attention, which they can then use to sell.

But they never actually gained the audiences’ attention.

They rented the stage but never performed for — never told a story to — the audience

Consequently the audience ignored the ad(s).

This is why market and media research firm Yankelovich can say that we’re exposed to 362 “actual advertisements” per day* but…

- only peripherally “note” 153 of those ads, and…

- only gain conscious awareness of 86 of them, and finally…

- only halfway remember 12 of them.

In other words, you only pay serious attention to 3% of the ads that you’re exposed to.

Because there’s no story provided by the other 97% of ads.

The advertisers bought exposure, which they assumed would get them attention, and then they tried to sell, without the benefit of story.

But back when advertising built fortunes, ad guys knew better…

David Ogilvy on Story Appeal

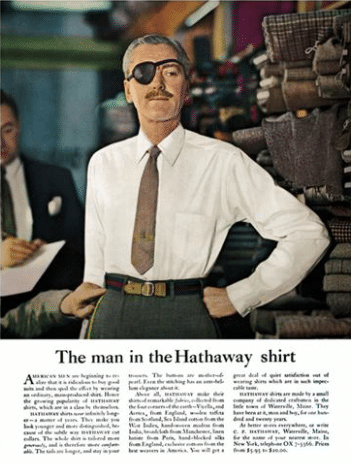

The ad to the left is one of many campaigns that cemented David Ogilvy’s reputation as the greatest of the Madison Avenue Wizards.

And what you’ll notice is the deft use of story appeal in the form of the model’s eyepatch.

And what you’ll notice is the deft use of story appeal in the form of the model’s eyepatch.

Here’s how Ogilvy describes the phenomenon in his book, Ogilvy on Advertising:

“The kind of photographs which work hardest are those which arouse the reader’s curiosity. He glances at the photograph and says to himself, ‘What goes on here?’ Then he reads your copy to find out. Harold Rudolph called this magic element ‘Story Appeal,’ and demonstrated that the more of it you inject into your photographs, the more people look at your advertisements.”

‘The eyepatch injects the magic element of ’story appeal.’”

Story appeal is that which compels the viewer or listener to need to know the “story” or context behind the phenomenon he’s witnessing.

“What goes on here?”

The model in that product photo, Baron George Wrangell, didn’t wear an eye patch. That was Ogilvy’s idea.

Ogilvy even brought the eye patch to the photo shoot, with the intention of injecting story appeal — Who is that guy? How’d he lose his eye? What’s his story?

Because Ogilvy knew that the story appeal of the photo would gain him the magazine readers’ attention.

Attention that his copy could then retain.

And he could then use that sustained attention to make the (emotional) sale

Story —> Attention —> Sale

Ogilvy knew better than to presume a mere ad placement guaranteed him the readers’ attention.

Chick-Fil-A Understands Story

Way back in 1995, Chick-Fil-A couldn’t afford electronic media in the Atlanta market, and faced better-known competitors with (much) bigger ad budgets.

So they sought to break through via billboards.

And perhaps precisely because they couldn’t afford to “buy” attention, they fell back on story.

Their billboards didn’t presume anyone was paying attention, and didn’t shout out a sales message.

Instead, their fantastic 3-D billboards (created by The Richards Group) are a perfect case study in “Story Appeal.”

Seeing the misspelled, hand-painted sign, you can’t help but wonder:

“What goes on here?”

And then you see the 3-D cows with paint brushes in hand.

That’s when your mind fills in the blank and “gets” the story…

Those cows created the sign to save their lives.

Boom! The story has your attention. And now the cows can sell you on their message and mission.

Story —> Attention —> Sale

It worked like a charm.

Chick-Fil-A grew from a regional brand to become the 8th largest restaurant chain in the U.S. and Chick-Fil-A outsells KFC by 50% — despite having fewer stores and remaining closed on Sunday.

So either your ads have story appeal, or they’re going against the Story —> Attention —> Sale cycle.

And if they’re going against the cycle, you’re wasting your ad budget.

Want to break out of that dysfunctional cycle and jump into the Story —> Attention —> Sale cycle?

Contact me and we’ll create a story-based ad campaign to grow your business to the next level.

Continue to Part 2: Creating Story Appeal On Demand

*P.S. You’ll often hear Yankelovich referenced in relation to the claim that people are subjected to 5000+ “brand exposures” per day, rather than 362 actual adverts. Both numbers are true. The difference is that the polo pony on your shirt, as well as the label on your orange juice or milk carton all count as “brand exposures” that add to that 5000+ number. Whereas only actual advertisements count towards the 362 number.

- Are You Paying for Too Much for the Wrong Keywords? - July 15, 2024

- Dominate Your Market Like Rolex — 4 Powerful Branding Lessons - July 3, 2024

- Military-Grade Persuasion for Your Branding - June 25, 2024