If you don’t get the audience’s attention, your message will not be heard. The concept is simple, but how do you actually do that?

In this episode of The Wizard’s Roundtable, I’m joined by Orlando Wood, Chief Innovation Officer at System 1 Group in London.

His book Lemon and subsequent short film Achtung! outline how we’ve lost customer’s attention over the years, and how to get it back.

Runtime approx 22 mins

Helpful Links:

Addressing the Crisis in Creativity: https://youtu.be/XUXYRf5O5T4

Achtung! https://youtu.be/6RU0WzFkhJg

System 1 Group: https://www.system1group.com

Transcript lightly edited for clarity.

JOHNNY:

Bill Bernbach said if your advertising goes unnoticed, everything else is academic. David Ogilvy said it takes a big idea to attract the attention of consumers unless your advertising contains a big idea. It will pass like a ship in the night. And you’ve heard us say that we believe entertainment is the currency that will purchase the attention in the minds of a too-busy customer.

So we all agree that getting attention is important. How do you get it? How do you keep it more importantly? My guest today is Orlando wood. He is the author of a book called Lemon. How the advertising brain turned sour this past fall. He released a film called October at the effectiveness works global conference, and it demonstrated how a conspicuous lack of character place and time could be at the root of the poor performance ad campaigns have been having over the past 10 to 15 years. He is the chief innovation officer at System 1 Group, a firm that among other things measures the emotional content of an ad campaign. And that helps measure potential effectiveness.

So we all agree that getting attention is important. How do you get it? How do you keep it more importantly? My guest today is Orlando wood. He is the author of a book called Lemon. How the advertising brain turned sour this past fall. He released a film called October at the effectiveness works global conference, and it demonstrated how a conspicuous lack of character place and time could be at the root of the poor performance ad campaigns have been having over the past 10 to 15 years. He is the chief innovation officer at System 1 Group, a firm that among other things measures the emotional content of an ad campaign. And that helps measure potential effectiveness.

Now this problem with attention didn’t just occur overnight. It’s been something that has been slowly growing year after year. So where did it start?

ORLANDO:

I think you’d probably have to say that the digital world has something to do with it. You know, we’ve been through enormous changes in the last 15, 20 years in how we do business. Societal changes too by the way. But changes in technology have led to certain things becoming easier and quicker, but at the same time leading to other — perhaps unforeseen or unintended, or perhaps even intended — consequences such as the speeding up of creative work. So, you know, we used to have perhaps a few weeks to create a campaign. Maybe longer, maybe months. And now it feels as though, you know, you only have days, maybe even hours in some cases. So that speeding up of things is, you know, you need time to sort of think and process and…

JOHNNY:

Research and all the other things…

ORLANDO:

Exactly understand the problem. Understand what you’re truly trying to do and how you relate to your competitors and everything else. So, you know, it takes time to make really great work. But also I think it’s led to this ability to standardize so you only need to make one ad across lots of geographies. And when you have this sort of standardized global ad, you know, it’s an ad that’s supposed to work everywhere, but in fact probably ends up working nowhere.

JOHNNY:

It’s a good time to be in the template industry. Isn’t it?

ORLANDO:

Quite. Because you can’t draw on those local cultural references, you know. You can’t show people talking or interacting, you know. Anywhere you show it has to be pretty generic so it could be sort of vaguely applicable anywhere rather than, you know, showing people in the street in London or wherever else it might be. So you know, it…

JOHNNY:

It loses a sense of humanity…

ORLANDO:

Right. One of the things that I talk about in my more recent work, ACHTUNG! I talk about the importance in advertising of character, incident, and place. How they hold attention. How they elicit emotional response and they’re the sort of features that help to drive long and broad effects. And, you know, it was very difficult to find in ads today. I mean, there are obviously exceptions that can be described by asking and answering those three questions. Who’s involved, what happens, and where is it set? And those things sort of route us to where we are, to our surroundings. They’re what make people pay attention to things. So yeah, the sense of longing and belonging, you know, is sort of given away. And it’s still there in the general public, but you don’t see it much in advertising.

JOHNNY:

Is there a sense, Orlando, of which is the chicken and which is the egg? In other words, did the business community say, “I want this fast and now, and we need to move. I don’t want any creativity, I want a template that I can count on?” Or did the advertising industry offer it up and say, “This is an easier way for us and for you?”

ORLANDO:

Well, I think it’s a bit of both, isn’t it? I think clients have obviously embraced this fast, new world. I think they’ve also put a lot of pressures via procurement on agencies. The big network agencies, I think you know, reduced costs trying to improve efficiency and productivity, but at the same time. Of course, that leads inevitably to the removal of very senior talent and experienced talent. It’s a bit of both. And technology certainly has something to do with it. But I think that there’s a been a broader shift in our habits of thinking. And I think you see this in other periods in history. And that’s one of the things I do in Lemon, I look at how this is sort of happened before.

JOHNNY:

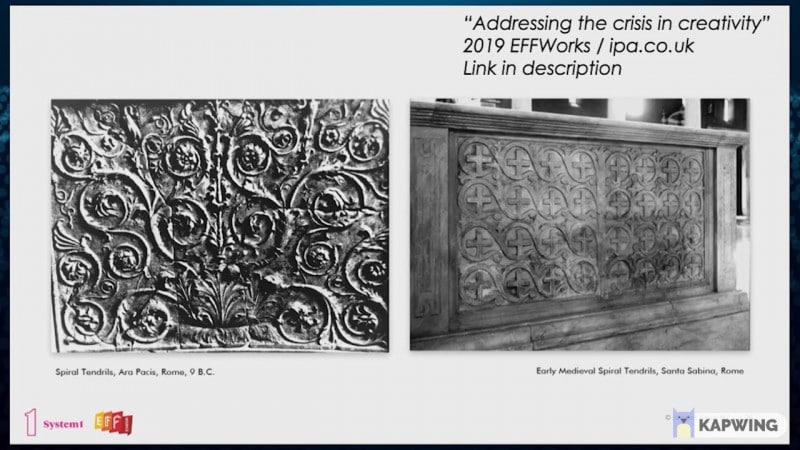

Yeah, that’s an interesting part of Lemon, where you show how art has gone from this very organic and maybe incongruent feel to a very flat and symmetrical feel. And then back again…

ORLANDO:

From these spiral tendrils here, that depict nature, as it sort of is with depth, a bit of asymmetry and a sense of flow, towards this flattened devitalized symmetrical and an emphasis on signs and symbols, the vine and the crosses. We go from mosaics of people who were talking to each other in dialogue with depth, with light and shade towards unilateral mosaics, communicating me at you.

JOHNNY:

Are we in a cycle? Does it come back?

ORLANDO:

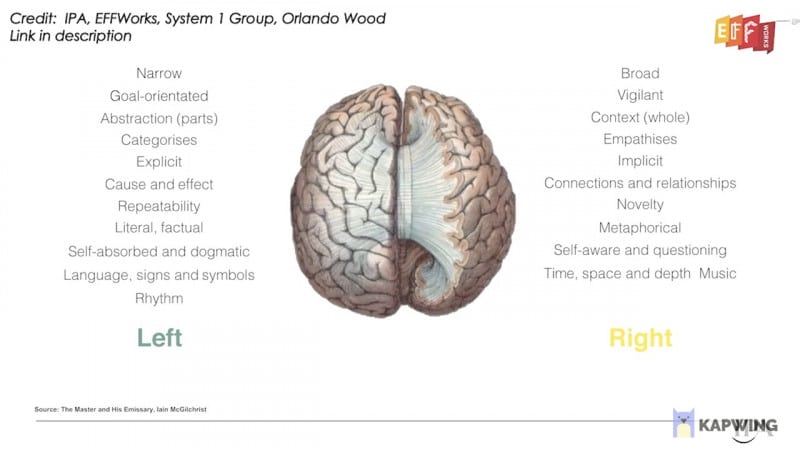

Let’s hope so, I mean, it normally does at some point. Of course I explain in the book why. Drawing on the work of a brilliant scientist psychiatrist, psychologist, and neuropsychologist called Ian McGilchrist, who talks about the two hemispheres of the brain and how they attend to the world. And you know, we’ve had this sort of misguided notion since the sixties that perhaps the left and the right brain might do different things. It’s not so much, they do different things. They do things differently. They’re different modes of attention. The left brain is very narrow and goal-orientated, and it breaks things up into smaller parts. It likes to categorize things, categorize people. It’s very explicit. Things are either truths or lies. You know, the obsession with truths and lies and facts at the moment is everywhere — and a sense of paranoia that we don’t actually know what the truth is.

All of this comes with the left brain. And by the way, anger lateralizes to the left brain too. And so people are adopting dogmatic positions, entrenched, and can’t see the other side. So the left brain is very rhythmic, likes rhythm, it can only really discern rhythm and music. It doesn’t have a sense of time or space or depth. But the right brain brain is broad and vigilant by contrast in its attention. And it sees them as the world as it really is everything in context. It can understand gestures, intonations, accents, you know, the embodied nature of the world and how we feel it. And it understands time and space, music, and it can understand two opposing thoughts could be true at the same time. So it can understand metaphor for humor, all of those things that make us people, that make us human.

JOHNNY:

Right, and that’s the entryway. Right? That’s the way to get into the brain.

ORLANDO:

That is the way in. Exactly. Yeah because the right brain presents the world to us. And then the left brain tries to unpack it and then re-present it back to us in a sort of simplified, flattened, ordered kind of way.

JOHNNY:

It feels natural, sorry to interrupt —

ORLANDO:

No, please do.

JOHNNY:

It feel natural then for business or an advertiser to say “Well let’s logically lay this argument out like we’re putting together a documentary or something.”

ORLANDO:

Yeah, exactly.

JOHNNY:

Yeah. But documentaries don’t persuade, that’s not their job. And then you are almost leaving too much in the hands of the consumer to put the piece together and come to a conclusion.

ORLANDO:

And it assumes an inherent interest in what you’ve got to say. Hey, and that’s actually another thing. The digital world has enabled us to target much better than we ever could in the past. And with that targeting, and ability to target, comes gradually a kind of implicit assumption that whoever is looking at this is going to have some interest in this category and this product. You can’t assume that the audience’s interest is a given. Particularly if you’re trying to draw in people who are outside the immediate-buying mode. You know, if you’re trying to look at people to grow your salience and brand band look for longer and broader effects, then relevance isn’t enough. You have to entertain. And that’s one of the things that I think I mentioned in the book.

JOHNNY:

And you have to entertain to get that saliency. Is that a fair way to say that?

ORLANDO:

Yeah, because emotional response does three things. It orientates our attention, first of all. Secondly, it helps to put things in long-term memory. So it helps with memory and coding. And thirdly, it helps us to make a decision quickly in the future because it promotes certain brands, makes them more salient if we’ve had some sort of positive experience of them. And it deemphasizes others that we haven’t had positive experiences or so, you know, it puts you at the top of the shortlist.

JOHNNY:

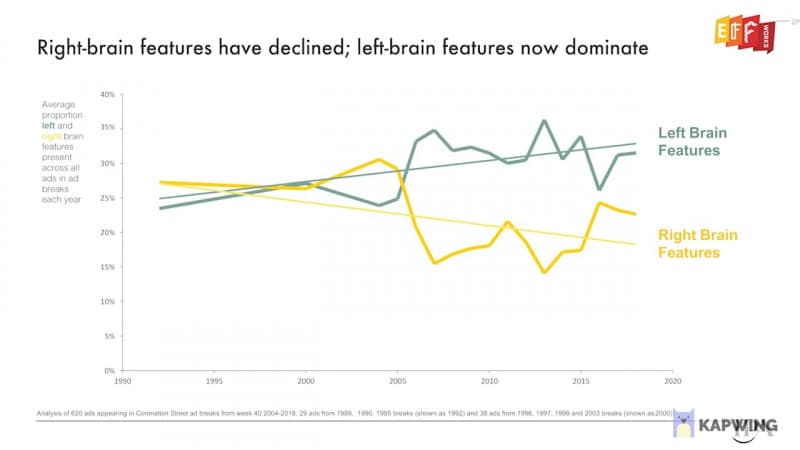

You’ve also demonstrated a correlation between more right-brain focused advertising and their effectiveness. And the IPA has also shown that advertising campaign effectiveness has been going down substantially year over year. Is it cause and effect? Does one lead the other, or are we such a distracted society that we aren’t taking time to absorb all these things coming at us?

ORLANDO:

In my view they’re certainly interlinked. If you look at different data sets over the same time period there’s something congruent across them all. And I suppose in around 2005, 2006, that sort of time period, 2007, around then… In Lemon, I say 2006 as that’s what the data suggests there was this change in on the one hand creative style and on the other this reduction in effectiveness. And you’ve also got different types of media buying as well, going on in this, in that, in that sort of period, everything points in the same direction and all of these things are happening at the same time. And when you look at the relationship between what I call right-brain features: characters, live time, place, all those sorts of things, and emotional response and attention. You can see that they’re the things that are driving those sort of responses in people. And they’re precisely the things that have been disappearing and being replaced by rhythm and words and short, sharp cuts, and you know abstraction and flatness.

JOHNNY:

I see a lot of spinning mobile phones… [Shows repetitive commercials: camera circling a Samsumg / Motorola / LG / Google / Apple as features show up on screen and music plays] Mobile phones like to spin (chuckling).

ORLANDO:

That’s the other thing, there’s an emphasis on things. The left brain likes things. It can’t really understand people. And so there’s an emphasis on things. And also there’s this sort of frontality that you see a lot in advertising now. A bit like us now, looking at each other square — almost a stare, like an adversarial stance — that the advertising is taking. That is extremely off-putting. I think it’s a bit of a warning sign that all is not well in the world. You know, the collective mental psyche is going through difficult and disorientating times.

JOHNNY:

It’s like we’re due for another jazz movement or something…

ORLANDO:

Well, let’s hope it’s something as positive as that.

JOHNNY:

That’s true. Yeah. We could shake the snow globe up in a different way too. So if you don’t mind, spend a little time on those right-brain features you mentioned. Because I think that’s really important…

ORLANDO:

Yeah my shorthand at the moment is character, incident, and place, because they seem to be extremely important in holding attention and generating an emotional response. And then what you might describe as storytelling, although storytelling is a bit of a wishy-washy word if you ask me. Everyone has a different interpretation of what that means. You know, can a building tell a story? I’m not sure it can in the traditional sense. So character, incident, place, seems pretty close to me to what we mean when we’re talking — in audio visual terms — about a story. That’s not to mention a number of other things that I talk about in the book Lemon.

So a sense of live time, knowing glances between characters, the stuff that the right brain picks up on, you know, that it sort of intuits. These implicit and implied things, a wink, a glance, body language, facial expressions, accents. All of that stuff that’s about the embodied world and how we understand each other beyond the words, that’s all very important. I talk about music in the book as well, and the importance of that, and things have become increasingly rhythmic. So very rhythmic beeps against these very short sharp cut ads, as opposed to music against an unfolding drama in a real place. Or somewhere that approaches the real world, you know, it may not be exactly this world, but it’s of this world.

I talk also in the book about the importance of characters and recurring characters, what I call Fluent Devices. A bit like the Geico gecko. These sort of recurring characters that are used many years very successfully. The importance of those for recognition, for emotional response, for attention even in digital in feed formats — they’re very good at attracting attention and holding it. And also those sorts of scenarios that are repeated over what we used to call a campaign. So, you know things like Snickers, “you’re not you when you’re hungry,” that’s also a fluent device. So these things really helpful at driving long and broad effects and also reducing price sensitivity. But they’ve been disappearing as I show in the book.

JOHNNY:

And what you demonstrate so well Achtung! is that this — to use an overused phrase — it’s simple, but not easy. The things you’re speaking about there are intuitively the right thing to do. It’s not necessarily easy to create characters, create a storyline, but holy cow, it’s so much more powerful.

ORLANDO:

Yeah., that’s right. And you know, it’s much more easy to remember as well. Easier to notice, easier to remember. And actually, you know, it’s important — kind of on another level cultural — glue that holds everything together. You know, they’re common reference points that suddenly have sort of disappeared or fallen off the map

JOHNNY:

When you make the argument of thinking long-term, you know, the Binet and Field Long and Short: you’ve got to have both but we’re very obsessed with the short term. Now, what’s your go-to argument, or what is it you describe to business owners or advertisers when you say “Yes, of course, we need to take care of the short term, but hold on because you need to be here tomorrow as well.”

ORLANDO:

Yeah. Well those long run broader effects are ultimately more important and they help the short term activation advertising to work much harder as Peter Field has shown. I point to some of the evidence in the book, Lemon, that looks at what happens over a longer time period, and the relationship between extra share of voice and share of market gain. And there is this by and large, pretty established relationship between how much you’re spending relative to your size (relative to the competition) and market share growth the following year. And when you overlay on that, this kind of emotional response to advertising, you get a much stronger and better explanation of market share movements in that following year. So it’s like a long-term measure. We’ve got so many short-term measures at the moment that promote a certain kind of advertising that might drive quick web effects, but it’s not going to do much more than that.

And if you’re looking for that longer term growth, and investors often are, then you need to think about the kind of work that’s going to generate that emotional response. It’s quality, not just quantity of advertising that matters. And quality of advertising can be reasonably well explained by some of the features I describe and this mechanistic left-brain advertising. You know, very rhythmic and pretty close up to things. You’re kind of uncomfortably close to the product, perhaps shown out of context with no real background, just bits of people and things.

JOHNNY:

No faces.

ORLANDO:

And you don’t see full faces. You see just the lips, or just the eyes, or just the hands. The left brain likes to break things down in smaller parts, including people. So that’s what you see a lot of and it’s just tiring… wearing and disengaging, you know, to have so many things up close without any broader sense of context.

JOHNNY:

If you’d like to learn more about Orlando’s work, you can go to system1group.com. And to learn more about the IPA, the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, go to ipa.co.uk. And I’m Johnny Molson. If you have any questions or comments, leave them in the box below, or you can send me an email, Johnnymolson@wizardofads.com. And don’t forget, these episodes are also a podcast that you can listen to. Just subscribe wherever you get podcasts.

- Marketing Has a Physics Problem - December 3, 2025

- AI is OK - August 14, 2025

- Emotion in Advertising Equals Dollars in Business - December 3, 2024