Seems like every marketer’s dream is to advertising a product or service with a magic-bullet-style Unique Selling Proposition (aka, USP).

But the vast majority of businesses don’t have one big differentiator.

They usually DO have half-a-dozen or more smaller differentiators, although they may not see them as worthy of mentioning individually.

To the business owner, these small differentiators get lumped together as the aggregate effect of “giving a damn” and “craftsmanship.”

The extra effort and steps and pains decent people take to ensure top quality.

It’s why they respond with “we care” and “we do a better job” when asked, “what makes you different than your competitors?”

Bad marketers roll their eyes at this and presume the client to be no different than their competitors, who they’re sure would make the same claims.

But great marketers are capable of turning “quality,” “craftsmanship,” and “caring” into an ad campaign that’s both:

a) True to the genuine character of the company, and

b) Capable of driving rocket-ship growth.

Let’s take a look at how that’s done.

Differentiation On a Sliding Scale

In an early article I made the case that differentiation isn’t binary.

It exists on a spectrum.

And this is especially important when it comes to smaller differentiators

First because these smaller factors are ideal candidates for preemptive claims.

As in it doesn’t matter if other companies also do it, if you’re the only one advertising that you do it.

As in it doesn’t matter if other companies also do it, if you’re the only one advertising that you do it.

Second, because the total “talent stack” of all the elements together often can be unique, even when individual elements aren’t.

And that goes double when you use the talent stack as proof of values rather than solely as differentiators.

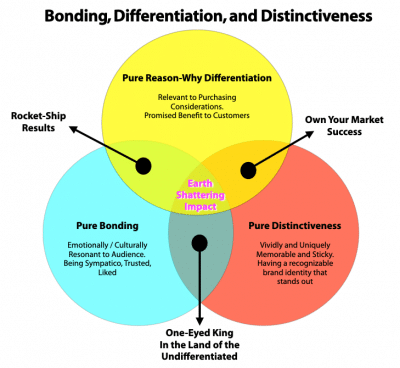

In fact, in that same article, I showed the Venn Diagram to the right, indicating that powerful advertising results were usually the result of a two-out-of-three overlap.

And it’s the overlap between Bonding and Differentiation that’s often the sweet spot for “Caring and Craftsmanship” companies.

Coors Brewing as Caring and Craftsmanship Case Study

In the mid-80’s Coors created an ad campaign that perfectly employed a Bonding-and-Differentiation strategy.

See, by 1980, Coors was still a regional brand, limited to an 11-state footprint, and operating out of a single brewery.

And while that did help to create Coors’ “cult beer” status, it also limited sales.

So in the early 80s, the Coors family decided to go national.

Which meant they had to give up a long-time family tradition of refusing to advertise their product. “A good beer sells itself” was actually a family motto.

Nevertheless, by the mid-80s they got set up for national distribution and launched a national ad campaign featuring spokesman Mark Harmon.

And boy did the ads work.

The campaign used a half-dozen smaller differentiators to build up “quality” and “caring” as what set their beer apart from Bud and Miller, while bonding with viewers over those same values.

From 1984 to the end of ’85 — the first full year of the campaign — Coors increased sales from from $1.1 Billion to $1.3 Billion. By 1989 they were up to $1.8 Billion in sales.

And Coors accomplished that while spending one third the ad dollars of their chief competitors, Budweiser and Miller.

So let’s take a look at the ads and then break down exactly how they implemented their Caring and Craft campaign.

Small Differentiators as Proof of Shared Values

In the first ad, Coors introduces their first differentiator: their then-unique cold filtered brewing process.

To be sure, Cold Filtered is a great differentiator.

So good that the temptation would have been to lead with and over-rely on Cold Filtered as a USP.

What makes that first ad great, though, is that they use this differentiator as a proof of values, rather than the end-all, be-all selling promise.

Yes, cold-filtering makes a difference, but it’s only one of many things that Coors does different because their aim is different — they value craftsmanship over mass production.

Hence the need for a Charismatic, “All-American”-looking spokesman on a ranch in the Rockies talking to you about cold filtering — this is a bonding move as much of a differentiation play.

Coors wants you to feel like they are your kind of people, making a beer that’s sure to be your kind of beer.

That’s why Coors is able to move from Cold Filtering in one ad to Aging in the next. And then from Aging to Barley. And from Barley to “the time it takes to brew.” And so on.

It’s also why Coors was able to throw in an occasional ad focused solely on shared values, like the one about rugged individualism.

Also, keep in mind that this Coors campaign was indeed a campaign, rather than a single ad

And that allowed each ad in the campaign to dramatize one factor as an example of values-in-action — all while bonding with customers over those same values.

This is a much stronger play than having a single ad attempting to cover all of the differentiating factors in one go, which is the typical move for newbie advertisers.

It’s also a far better move than relying on a single USP for differentiation, not least because most every differentiator can and will be copied, sooner or later.

As was the case when Miller introduced Miller Genuine Draft, featuring their “cold-filtered four times” brewing process.

What About YOUR Advertising?

Are you frustrated by marketing bozos who insist that you have to have a single, unique differentiator?

Or, who, in the absence of that magic USP, fall back on irrelevant, “wacky” creativity?

Or worse, roll their eyes at you when you tell them that you actually care about your customers and your craft?

If so, it’s time to partner with an ad team who knows how to advertise a company like yours.

- Getting a Foot in the Door — Of Perception - November 27, 2025

- What Digital Superstars Know About Offline Advertising - November 17, 2025

- Unmistakable: A Tale of Two Boots and Branding Done Right - November 8, 2025