Johnny Molson: What’s the lifetime value of a customer to your business? It’s one of these magic, Holy Grail type numbers that businesses and marketers like to look at. If we can figure out what the value of one customer will be over a lifetime of purchases doing business with you, then you can start to do some pretty interesting calculations on the front end. How much money do you want to apply to acquire that first customer? But it comes in conflict with the idea of getting business in now. It’s this delicate balance of thinking long term, but also taking care of the short term.

To talk about that today I’m joined by two other Wizard of Ads partners. Dave young is in Tucson, Arizona. Chuck McKay is in Indianapolis, Indiana, and I’m here in Springfield, Illinois. And we’re going to start with Chuck McKay, just talking about the concept of lifetime value of a customer.

Chuck McKay: You want to know (1) How much does a customer spend each time? (2) How many times is he going to spend that from his first purchase to his last? And that is his lifetime value. How do you know when the last purchase is? Depending upon what it is you’re buying, you can say, “Well, if he hasn’t bought anything in the last year, he’s no longer a current customer.” What if it’s a refrigerator.

Johnny Molson: Right…

Chuck McKay: You don’t buy one of those every year. So there’s a little bit of juggling that is necessary for any of this. But basically once a person becomes a customer, how much can we expect him to spend with us? That’s the definition. Here’s the part that gets really interesting. A former boss of mine when I was a much younger man said, “You know, you can grow your company so fast you can go bankrupt.” I replied, “Really? How does that work?” “Well, you start growing and you need to add more staff to handle the new customers. But you don’t have the new money coming in as fast as your new payroll is going out, so that can kill you. And if you’re selling on credit, that can kill you.”

That’s the thing. If you are not careful, if you’re thinking “Oh, here’s so much this is going to be worth to us long long-term, but you don’t look at the cashflow… In the meantime, you can literally bankrupt your company by growing too quickly.

Dave Young: One of the things a lot of business owners don’t take into account when they look at something that’s seemingly as simple as the lifetime value of a customer calculation is your product purchase cycle. And it makes it super hard to calculate it depending on what that cycle is. If you’re a restaurant and the lifetime value of a customer is if I can get them coming in once a week, right. That’s pretty easy math. But if you’re an air conditioning company or roofer, how often do you need to buy a new roof for your house? So how do you calculate the lifetime value of a roofing customer?

Chuck McKay: Probably one purchase.

Dave Young: Probably. If you don’t take into account that product purchase cycle… I think the longer the product purchase cycle, the harder it is to come up with the calculation of what the lifetime value of a customer is when you’re just looking at that one customer or trying to do an average. Because you don’t know how long that roof is going to last. I mean, you can put a warranty on it or something, but are you going to get repeat business? They might sell their house first.

Johnny Molson: So there are instances where lifetime customer value maybe doesn’t even apply? I mean, I guess those are probably extreme situations where you only need a roof every 20 years. So you may only run into this once, maybe twice in your life. But we know we’re gonna need a bed every seven years and we’re going to get a car every two or three years. And that’s where that calculation of building that relationship comes in. So how do you solidify that relationship so it’s not just a transaction this one time. But that you’e still in their brain seven years from now, when they need you again?

Chuck McKay: Right. And what are you willing to pay for that first transaction to get that customer to begin with? Will you take a loss to get the first one?

Dave Young: It illustrates the beauty of home service companies putting together maintenance clubs, right? Where if you just buy an air conditioner unit and only call them when it’s broken. You calculate your lifetime value of customer that way, you’re going to get a wildly different number than if you’ve installed their air conditioner and you’re getting $24 a month from them so that they can stay a customer. You’re going to be seeing them once or twice a year. And I think it’s a little easier to assume that when this unit finally fails they’re going to be a repeat customer. If you can switch from being that one time transaction over the course of a decade or more, to being something where you’re selling them something all the time. I think then the calculation of a lifetime value of a customer makes a whole lot more sense. And it becomes a metric that can really have some value to track because you’re actually now doing things that are going to affect it in a real serious way.

Chuck McKay: How many businesses do either of you know that have gone whole hog with Groupon?

Chuck McKay: How many businesses do either of you know that have gone whole hog with Groupon?

Johnny Molson: Oh, it’s been a while since I’ve run into that. But boy, the ones that did really got bit in the ass because they got that lovely influx of people, but they didn’t make a profit.

Chuck McKay: Worse yet, when they went back to regular price, none of those discounted customers ever returned.

Johnny Molson: I think that brings up the Binet and Field 60:40 rule that’s been so important in the last few years in marketing. This idea that most of your marketing budget should be applied to brand building and doing these long term relational things. But you can’t forget that 30 – 40% that needs to speak to the transactional, to the now, otherwise, Chuck, as you say, you’ll go broke before you do that. And that’s a really delicate balance. What we’re seeing though, is that so many businesses, 70 or 80% of them are pushing for the transactional “Now” stuff at the expense of building their brand. And so you don’t have that relational thing living longer. Now Chuck, you said, should a business even be willing to lose a little bit on that first sale to get the second sale? If we’re going to use the Groupon example, you know, to extend that out, a business would be wise to use that as an immense data collection moment, so that they can talk to those customers again. “Hey, remember when you had that great meal, Hey, Rob, we had that great time…” So at least you can recapture some of those at a profitable price. But I think so many businesses used it just to be a quick hit.

Chuck McKay: Right. And I’m going to disagree with you, Johnny. Gathering a database of people who are not your customers is not going to accomplish much for you.

Johnny Molson: That’s a good point.

Chuck McKay: Okay, now I worked with a restaurant in Victorville, California years ago. I found a service that would give us a listing of all of the homes in the community that had been sold in the last seven days. And we sent letters out to them that said, “Congratulations on your new house. Let’s celebrate. I want to buy dinner for one member of your family.” Now this isn’t a cents off coupon. It’s not buy one, get one. It’s I’ll buy dinner for one member of your family. It’s a great investment on my part because when you come in and you try X, and we named several items… We said, “You know on Fridays people are driving clear across town for our clam chowder, it’s that good.” We know you’ll be back. And we track this thing carefully. We found that most people did come back. They really did, but we found that on that first transaction, after we paid for the purchase of the list, after we paid for the printing and the postage and the promotional food, we made a 7% profit. Every time one of those letters came through the door. It’s not a spectacular profit, but considering we were willing to lose money on that one, it turned out great.

Johnny Molson: Yeah. Did you have a sense of what percentage of the people who got the free meal came back?

Chuck McKay: Johnny, I can go through my notes and maybe tell you — it was 20 years ago.

Johnny Molson: Well, food was free 20 years ago, Chuck. I mean, my God (laughter). I think that’s an important part of the calculation is we know we’re going to get some people back. We’re not going to get them all back. What’s the likelihood… You just have to do that math and maybe do do the math three or four ways. If half of them come back, it’s this, if 10% of them come back, it’s that, but all those numbers better have a profit attached to them.

Chuck McKay: Here’s the thing. Who goes all by themselves to get a free meal at a restaurant?

Johnny Molson: Well, I’m lonely so…

Chuck McKay: It’s rare. Right? You take somebody else with you. And a new family that just moved into their new home, chances are you’re going to take four people total. So you’re comping one meal. Three you’re getting full price. And they still think they’ve got a bargain.

Dave Young: Yeah, I think there’s another calculation. I’ve seen businesses do things like Groupon and fail to really make sure that they’re crafting what that Groupon experience looks like with their staff. There’s a local art school here that we’ve had some association with. My daughter used to work for and they did a make-your-own-glass-objects Groupon. Well, there were a number of employees that when one of those came in the door, they kind of grumbled about it. “Oh, another Groupon…” And, rather than looking at it as, “Oh, here’s somebody that’s never touched molten glass before — never had this experience. Can we give them the type of experience that’s going to turn them into someone that wants to take a class? Can we give them the type of experience that’s going to turn them into someone that’s going to bring someone back the next time they come?” And when you have a wildly disparate reaction from your staff about embracing some kind of a discount or a Groupon, you’re going to get mixed results. I talk a lot about the experience. And you guys are familiar with the Advertising Performance Equation. And it’s basically your Share of Voice times your Impact Quotient of your ads equals Share of Mind. Your Share of Mind time the Personal Experience Factor of the experience you’re delivering inside your doors determines your Share of Market. Well, there exists in this formula — it’s not written out in the formula — but if you can up that Personal Experience Factor enough, it feeds back in to Share of Voice and becomes an accelerator for the whole calculation. And so you shouldn’t do anything like a Groupon unless you plan on delivering some kind of over the top experience. I mean, a free meal is a great one. It comes down to honing that experience. Which is what you have to be doing for figuring out customer lifetime value anyway, right?

If you can up the experience, the lifetime value of any customer goes up accordingly. And if you’re in a long product purchase cycle business, and you can’t figure out a way to turn somebody into an ongoing small purchase repeat customer, then you need to figure out a way to really up the experience of that one time in a decade that they’re going to come in and do business with you. You’ve got to figure out how to make that just knock their socks off so that you get that feedback. The experience loop feeding back into Share of Voice because they’re now telling people about you. And that’s the ultimate goal of really delivering a really good experience. It’s to increase the share-ability of your business.

Johnny Molson: And that’s the difference between adding value versus having a discount. If you can add value to something, you know, the home service businesses that are doing so brilliantly with the maintenance agreements… They just keep adding another thing “And, oh by the way, we’ll do this. Oh by the way, we’ll do that.” So that you’d be nuts to ever step away from it. But you gotta keep ahead of them and keep innovating. Because that’s the thing that’s going to build that bond between you and your customer. A discount isn’t going to build a bond other than to train them to wait for a discount.

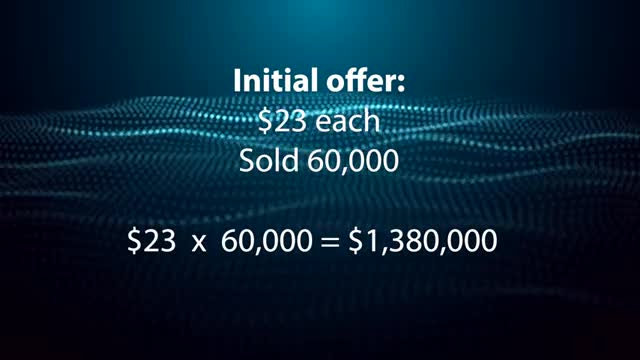

Chuck McKay: Jay Abraham quite a number of years ago told about a coin dealer that he worked with. The dealer got a starter set of coins. And with postage, it was $23. We sold them at cost. He did this ad campaign that said you could get started in coin, collecting with a new set of coins. And they are only $23 each and he sold 60,000 of those.

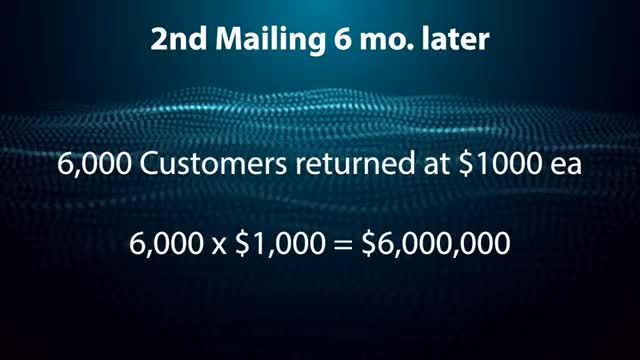

Okay. He broke even on almost $1.4 million worth of transactions. But within six months, 10% of them bought another thousand dollars worth of coins.

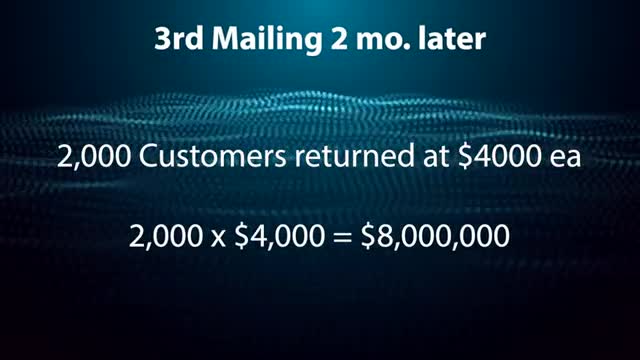

And two months after that, 2000 of the 6,000 that bought the second coins, bought another $4,000 worth of additional coins.

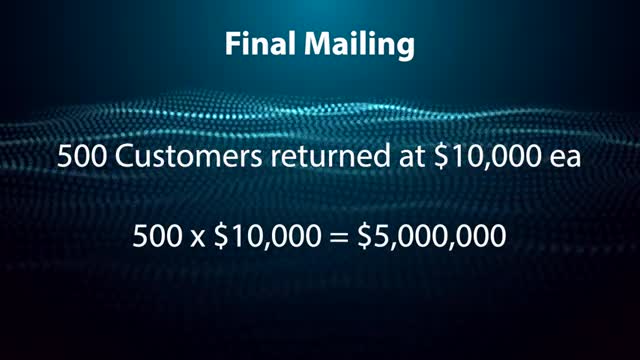

And finally 500 of the original 60,000 bought $10,000 worth of coins.

So his total profit on this thing, the mailing, profit worked out to be $19 million by giving away the first 60,000 of them.

Johnny Molson: And how amazingly valuable are those 500 people who made it through to the fourth mailing and were still customers. I mean, those are your golden people.

Chuck McKay: Those 500, you better know their wedding anniversary. The names of their kids. Which social clubs they belong to. You better send them a Christmas gift. It wouldn’t hurt to send them a card on their birthday. You better treat those people like the gold they are. But my point is this. there were backend sales to be made and you take the entire 60,000, only 500 of them turned out to be really, really good clients. But the entire 60,000 averaged $317 each. That’s the average of 60,000. They all spent $317 beyond the $23. Now that’s misleading because obviously some of them spent nothing beyond that, but we’re talking averages here. And so if you know you can keep on selling them and upselling them, even if it becomes smaller and smaller numbers, this is total lifetime value.

Johnny Molson: Even the second mailing where they sold 6,000 of them is nothing to shake a stick at.

Chuck McKay: Right.

Johnny Molson: Yeah. I mean, they started turning a profit at the second mailing, but they had to be willing to get burned the first time.

Chuck McKay: Well, they broke even the first time. So they moved almost $1.4 million at breakeven. If you can figure out ways to add to the lifetime value of a typical customer, you don’t have to make a lot of money at any given time because you have created a steady stream of income.

Dave Young: You know, I think you brought up a really great point talking about those 500 that spent 10,000 each. I mean, these are the heavy hitters. As you said, you better know their birthdays, their anniversaries, you better know them really well because they’re your most important people. And they’re the ones that are probably bragging and showing people their coins.

Chuck McKay: Are either of you familiar with RFM analysis, recency, frequency, and monetary value? Okay. I did this with an auto repair shop a number of years ago. We sorted his — I think he had 1700 active customers in his database. We sorted it by “When did they purchase last?” Somebody who purchased yesterday got a five. Somebody who purchased years ago got a one. And we broke it into what they call quintiles, equal groups of five. So the recent ones were fives. The not so recent ones were one. Then we did the same thing for “How many times did they buy from you?” And this was the frequency component, again from five on down to one. And finally, “How much did they spend on their repairs?” The biggest numbers got the five, the lowest numbers got the one. Then we just multiplied the value of each of those scores. Five times five times five is a hundred and quarter. One times one times one is three, right?

And I looked at it. I said, “If I were you, I would never solicit another purchase to this bottom 20%. I think you’re losing money. Every time they come in here, you’re definitely losing money if you invite them in. So you don’t necessarily need you to turn down their business, but stop inviting them.” We worked it out. I think there were 83 customers that made up something like 80% of his business. 83 out of 1700. Those were his golden customers. And then that was when I first said learn when their kids are graduating high school and send a gift. Make sure to send a bottle of wine on their wedding anniversaries, because these are the people that are making you very, very profitable.

Johnny Molson: What kind of questions or thoughts do you have about this? We’d love to hear from you in the YouTube comments, or send an email to Chuck, Dave, or to myself.

- 2024: The Year Digital Becomes “Traditional” - July 10, 2024

- MYTH: Everyone goes to Google first - June 26, 2024

- Sales Today or Salience Tomorrow? Yes. - March 14, 2024

- Bringing Newcomers into the Labor Pool - January 4, 2023

- Hire Veterans Reentering the Local Job Market - December 28, 2022

- The Personality Prescription, Part 14 – The Local Labor Pool - December 13, 2022

- Should I Buy Facebook Ads? - January 26, 2021

- The Recessionary “Share of Voice” Bonus - July 27, 2020

- A Divorcee, a Dentist and a Marketing Wonk Walk Into a Bar* - July 23, 2020